Little Cries: Fashion Jungle in Studio, Part I

The Fashion Jungle looking crafty in a 1984 publicity shoot. From left: Doug Hubley, Ken Reynolds, Steve Chapman, Kathren Torraca. Photo by Gretchen Schaefer.

“The Fashion Jungle is the other half of Portland’s one-two punch [along with Big House.] . . . Doug Hubley, Steve Chapman and Ken Reynolds all write and play perfect pop songs à la Elvis Costello’s first album or latter-day XTC. They have a seemingly endless supply of catchy hooks and provocative lyrics. With the addition of Catherine [sic] Torraca on keyboards, The Fashion Jungle have a full sound with which to perform their miracles. Trouser Press gave their four-song cassette good marks and I agree.”

— Seth Berner, “A Beat From The Street,” Sweet Potato magazine, Feb. 29-March 14, 1984

Go directly to music! Skip self-indulgent writings of old man!

It may seem strange to you young whippersnappers, but back in my day it was much more difficult to put recorded music out into the world.

Then as now, the means for distributing music outside the confines of live performance were rooted in a mighty industrial apparatus. But for decades the industry occupied itself largely with manufacturing and distributing containers for music — vinyl, cassettes, etc. — that by today’s standards held a disappointingly small amount of sound considering the space they took up.

While they were fairly priced for the consumer (at least until CDs came along), they seemed to cost plenty to produce, especially on top of recording expenses, and even more so if you aspired to any sort of production values. For my bands it felt prohibitively expensive, even as recently as 20 years ago, to have a bunch of recordings manufactured in any format.

Nevertheless, it was and is the pop musician’s imperative to make recordings. It was part of the contract. You might never be able to do it — my band the Fashion Jungle came pretty close to not being able to do it — but, like the Muslim’s obligation to visit Mecca, you didn’t question the expectation. And why would you? Having a record was proof of legitimacy. More to the point, we get into music to play it for people, and what better way to play it for people than to sell them a record?

For many of us, too, recording was not just a means to various ends (make money, make fans, make a reputation, etc.). Emotionally it was an end in itself. It was the mystery that, once penetrated, would answer all questions and solve all problems. It was the Emerald City. So many great things had happened in so many recording studios that just getting into one and cutting tracks was a compulsion beyond all reason. It was the world I thought I wanted to be in.

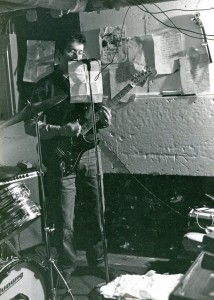

Hiding behinds words as usual, here I am during a Fashion Jungle rehearsal in the Hubleys’ basement. Jeff Stanton photo.

In the early ’70s I even tried to set my room in my parents’ basement up as some kind of studio, and I “produced” a recording, a collection of songs by a friend named Leah McKinney. All this based on a nearly complete lack of knowledge about studio realities.

The original Fashion Jungle didn’t last long enough to get into a studio (although in terms of spirit and recording sound, I like the demos we did — on a Sony reel-to-reel in my parents’ basement — nearly as much as the professional recordings that came later. Hear them here and here). But once bassist Steve Chapman, drummer Ken Reynolds and I had worked together for a while, we knew that we had the goods and that we needed to lay tracks.

I don’t remember how we chose Studio 3, which opened in 1981 in a little outbuilding behind the brick row houses on Park Street. Tim Tierney was the business manager and Tom Blackwell, the studio engineer — both of them kind souls who made our first studio-recording experience more than pleasant. We spent one evening there in August 1982 to record one song, which was all we could afford.

I still retain flashes of memory from that session. Nerves, of course. A tiny dim studio with zero atmosphere. It took some time to get a drum sound we liked, and the trial-and-error period included some experimenting with a water-filled snare drum that was one of Tom’s tricks of the trade. I don’t think we ended up using it, but it’s also true that the snare sound you hear (music below) is heavier, bassier, than Ken’s usual sound.

We recorded “Shortwave Radio,” laying down rhythm guitar, bass and drums in one pass, and overdubbing lead guitar and vocal. I don’t think we needed a lot of takes. The result was probably a third faster than it should have been. Studio nerves, maybe. The playing was good aside from the speed. We went in with no ideas about production or what sound we wanted. What we got was a very straightforward reproduction, clean, collected and businesslike.

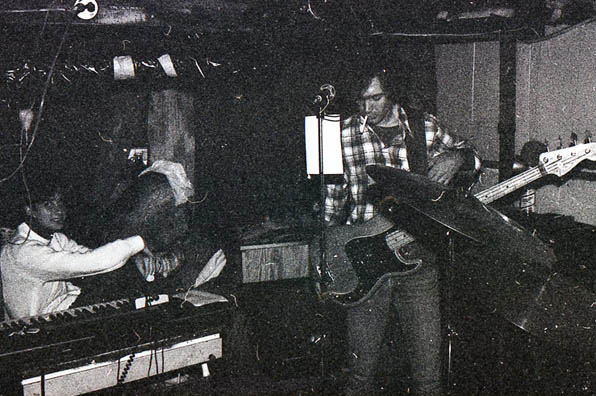

Kathren and Steve during a Fashion Jungle rehearsal in Ben and Hattie Hubley’s basement, 1983. Digital transfer from 35mm negative/Hubley Archives.

Afterward we stood around in the parking lot shivering and rehashing the session. It was an unseasonably chilly night (1982 was one of those years without much summer in Maine). I don’t think we were happy with the recording — we weren’t happy about something, in any case — and I’m not sure we ever did much with it. Maybe got a few jobs on the strength of it.

As previously noted in this space, keyboardist Kathren Torraca joined the FJ during the winter of 1983, resulting in the best-known FJ lineup. She was a quick study and we were ready to record with her by May 1983, a mere two months after her first live date with the band. Five of the six recordings below are from the three sessions that took place that month. Again we worked with Tim and Tom at Studio 3, which had relocated to Elm Street, in Portland’s Bayside neighborhood.

These were high times for the band and for me personally. I had finished classes at the University of Southern Maine the previous December, and Gretchen Schaefer, whom I had met at USM and partnered up with, and I graduated together early in the month (getting cold feet sitting in the Cumberland County Civic Center, where they had laid plywood over the hockey ice for our graduation; having beer, aquavit and croquet at my parents’ house; meeting for the first time Gretchen’s mother, May (appropriately enough) who came up from Connecticut in her olive-drab Ford Mustang for the occasion).

I had a full-time job in the clip library at the Guy Gannett newspapers, working 11 a.m. to 7 p.m. every weekday, and rehearsing into the evening a few days a week.

The FJ was playing out at few times a month — Geno’s, Kayo’s, Moose Alley, one-off gigs like a very lucrative date at Colby College that I wish to god I had recorded, because, as I recall, we were fabulous. (Maybe it’s better that I hadn’t recorded it.) And that date took place in between Studio 3 sessions. Man, we were pros! We were the bomb! It felt solid musically and personally. There was nowhere to go but up, and we were climbing fast. The May sessions fit that picture perfectly, at least as far as I can remember.

Gretchen with a new painting in the apartment on Preble Street, South Portland, that she moved into in 1983. The son of her then-landlord is now an engineer at The Studio, descendant of Studio 3. Hubley Archives.

Considering our limited studio experience, we acquitted ourselves well, needing a minimum of takes, overdubs and punch-ins. Gretchen came down after work at the Boys & Girls Club, bringing us sandwiches and beer, and coming away impressed with how businesslike we were. I have mental pictures of Tom Blackwell swabbing the heads on the 16-track recorder so often that it seemed like a tic or a reflex. I remember plying him with whiskey when we trooped into the control room to hear playbacks; I also recall Ken having to redo his “Entertainer” vocal because he kept singing, “She points her pank tongue at you” — instead of “pink tongue.” As Merle Haggard says, I guess I’ll just sit here and drank.

What I don’t remember is why we didn’t record “Old Masters” or one of Steve’s other songs, considering how good they were. Instead, we recorded one new song, the dance-clubby “Entertainer,” which Ken and I wrote; my “Groping for the Perfect Song,” from 1982; and fell back on two tunes from the pre-Steve FJ, Jim Sullivan’s “Censorship” and “Little Cries,” the first song I ever wrote for the FJ.

In the end, this second Studio 3 recording proved useful for getting work, and both the national music magazine Trouser Press and Portland’s own Sweet Potato reviewed it. But we never named, packaged or tried to sell it. Money was one reason. In addition, I don’t think we were that excited about the recordings. Like the August 1982 “Shortwave Radio,” we just played these songs too fast, excepting maybe “Entertainer.” Perhaps these were our usual tempos that worked on stage, where they were exciting, but not in the studio, where they came across as simply frantic.

By the same token, because — again — we had no clue what kind of sound to try for, Tom gave us a very straight mix that showed off our playing well but failed to achieve any particular emotional effect. I guess this is why there are producers. We thought we could do that job, but we thought wrong.

It was a dose of reality. They keep on coming. But still the recording imperative loomed over us. Phil Spector rode squirming on my shoulders. I guess The Recording Studio is one of those things that look huge and monolithic from a distance, but become smaller, more porous and more complex as you come closer.

You start out walking toward the Emerald City, and end up facing just another door.

Now for some music! Six recordings by the Fashion Jungle made at Studio 3, Portland, Maine, in 1982-83.

- Censorship (Sullivan) Long after “Dumb Models” and “Fashion Jungle Theme” had fallen by the wayside, Jim Sullivan’s two contributions to the 1981 FJ endured in the repertoire, a testament to the excitement and musical integrity he built into his songs. This Studio 3 performance is some tight!

- Little Cries (Hubley) Another entry from the class of 1981 that stayed with the Fashion Jungle till the end. Ken, Steve and especially Kathren shine here. Two years after we recorded it, this track ended up on the Studio 3-produced charity LP Maine Rocks for the United Way. In our sole appearance on vinyl, ever, we were among such local luminaries as the Kopterz, Scouts in Action, Devonsquare and the Jensons (whose founding drummer was my boyhood pal Tom Hansen).

- Entertainer (Reynolds-Hubley) One of two songs that Ken Reynolds and I co-wrote. As with “Dumb Models” and “She Lives Downstairs,” the genesis of the song was a morally anchored Reynolds lyric exploring some aspect of sexual politics — in this case, strippers. I created the melody and tweaked the lyrics a bit. It is actually pretty good club music. Parts of this song or this recording ended up as theme music for two media products: Gretchen Schaefer’s video-class project “Art Who?” in 1986, and a slide show about a play performed at the college where I work in 2006.

- Groping for the Perfect Song (Hubley) One of the first songs I wrote after Steve joined the band, this stayed with the FJ for the duration and cropped up again nearly 20 years later in the Howling Turbines repertoire. I derived some sort of early inspiration for this from David Byrne, but that didn’t last. This recording is a bit mechanical-sounding, and may be the weakest of the May 1983 stuff. Please buy it anyway, because we need the encouragement.

- Shortwave Radio (Hubley) This 1982 recording made at Studio 3 was the Fashion Jungle’s first venture into the studio. A song that enhances an early glimmer of self-awareness with lyrical touches that attempt to symbolize trains, radios and winter weather.

- Entertainer (Digitally modified!) (Reynolds-Hubley) The same original recording as the previous version, this has been enhanced, or something, with digital reverb to add the kind of atmosphere a song about striptease artists really needs.

“Censorship” copyright © 1981 by James Sullivan. “Little Cries” copyright © 1981 by Douglas L. Hubley. “Entertainer” copyright © 2012 by Kenneth W. Reynolds and Douglas L. Hubley. “Groping for the Perfect Song” copyright © 1983 by Douglas Hubley. “Shortwave Radio” copyright © 1981 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.

Text copyright © 2012 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.

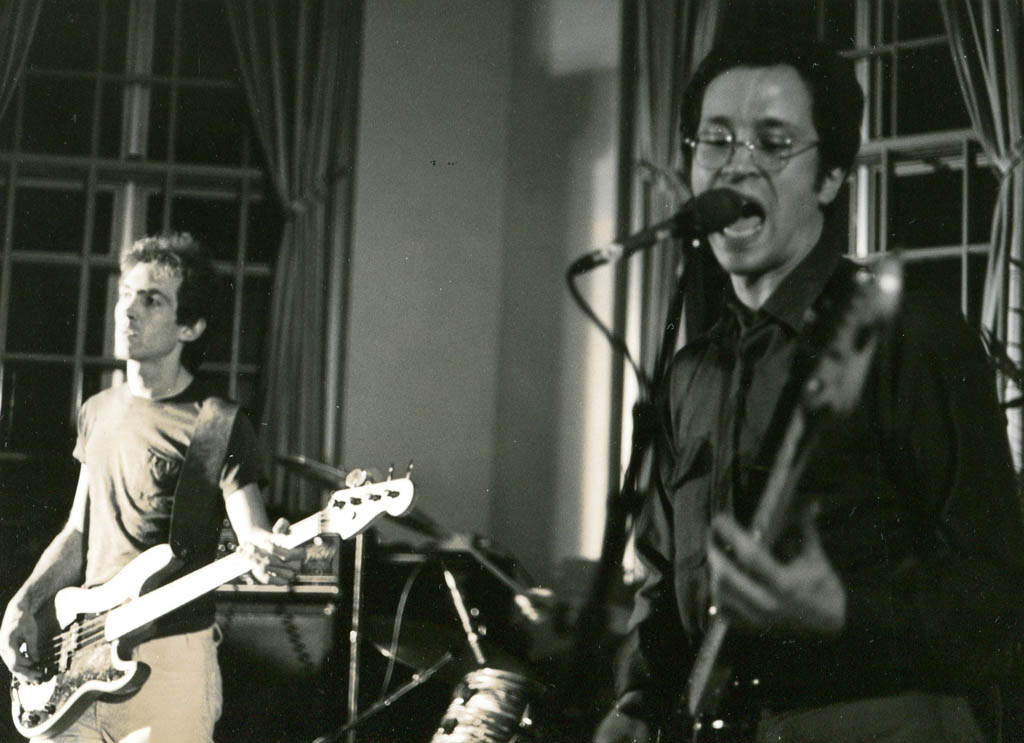

This time you can see my mouth — too bad! Steve and Doug during the May 1983 Colby College gig. Jeff Stanton photo.

Pingback: » Other Voices: The Fashion Jungle, 40 Years Later Notes From a Basement