Howling Turbines: Natty Gloves

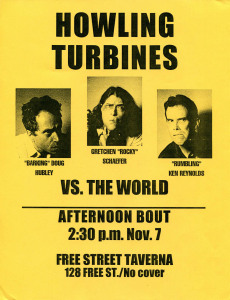

The Howling Turbines looking skeptical in an early publicity shot by Jeff Stanton, circa 1998. From left: Doug Hubley, Gretchen Schaefer, Ken Reynolds. Hubley Archives.

Enjoy the champagne-bubble sounds of Howling Turbines on the Bandcamp Internet!

Gretchen Schaefer and I are Louis Jordan fans.

So we were pleased, if surprised, by Ken Reynolds’ invitation to see the jukebox musical Five Guys Named Moe, based on Jordan’s jumping R&B, at the Ogunquit Playhouse in August 1996.

Ken seemed to take the theme quite seriously in this outtake from the 1998 boxing-poster photo session. Hubley Archives.

Surprised in part because Gretchen and I almost never go to musicals, but in larger part because the invitation from our longtime friend and former bandmate seemed like some kind of overture. “Is Ken asking us on a date?” we wondered.

I have known Ken, who is a drummer, since 1975. We met while working in the stockroom at Jordan Marsh at the Maine Mall, and found that our senses of humor really meshed. Three Stooges and Monty Python seemed very insidery in Portland, Maine, in the mid-1970s. We became good friends.

Doug Hubley strikes a pose that would intimidate even Wally Cox in this outtake from the boxing-poster session. Hubley Archives.

Through all the musical comings and goings, our longtime friendship with Ken had remained solid. But Ken’s invitation to drinks, dinner and a show (his family had season tickets at the playhouse) was an order of magnitude or two higher than our crowd’s usual frolics.

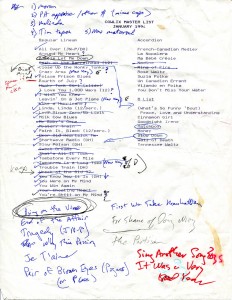

Gretchen Schaefer and I were calling ourselves “Howling Turbines” before Ken Reynolds returned as drummer. This song list bridges the two periods; the songs in black ink, we learned with Ken. The acoustic material of the interrim, such as Leonard Cohen’s “The Bells” (listed here as “Take This Longing”) didn’t last into the Turbines. Hubley Archives.

It was a fun occasion on a warm sunny day. We had gin and tonics at Barnacle Billy’s and dinner somewhere nice. Five Guys Named Moe — Gretchen’s and my introduction to the Ogunquit Playhouse — was mostly music with a minimum of contrived plot, so we liked it. (Mop!)

The occasion gave us more time to talk than usual and it was good to get caught up with Ken. I remember sitting in the sun on Barnacle Billy’s patio as Ken told us that he had taken up drums again, performing at a church. He was happy to be playing although the congregation was fractious and, I think, split up either just before or just after Ogunquit.

In the months after Jonathan and his wife, Nancy, lit out for Indiana, Gretchen and I tried out new material, from the Carter Family to Leonard Cohen, and also set the electric instruments aside and played acoustic guitars — anticipating our current band, Day for Night, by about 10 years.

In between the Boarders and Day for Night, though, there was another electric (and how!) band. I can’t remember the specifics, but sometime between our Ogunquit evening and our first rehearsals in early 1997, the three of us agreed that it would be a good idea for Ken to come back. And the Howling Turbines were born.

Howl

Ken hauled his drums back down into the basement in February 1997, 20 years to the month after he and I first started making music together. I remember the distinct pleasure I felt as the three of us got the ball rolling again. We knew each other well, personally and otherwise, and it didn’t take long to find our sound.

Which was not the Boarders’ sound. The two bands shared a format: the classic three-piece lineup of bass, drums and guitar. They shared a certain amount of material, and they shared Gretchen and me. But the sonics were quite different.

Much of the difference, of course, had to do with the drummers. Jonathan and Ken brought clearly

contrasting, if equally effective, approaches to

making the three-piece format work.

Your author in a film selfie, shot in the bedroom mirror in 1999. Notice the Concord Coach schedule tucked in the mirror frame in case we needed to make a quick getaway. Hubley Archives.

With perhaps a decade of experience over Jon, by this point Ken was a much sparer stylist. He brought a relentless focus to the beat and an almost mathematical sense to his fills. Interestingly, Ken also worked his tom-toms, especially the floor tom, much harder with the Turbines than with our previous groups.

Their kits sounded quite different, too. Jon was playing a Yamaha set that had a mid-weight sound. Ken, meanwhile, had left his original Ringo Starr-model Ludwigs behind and brought in a massive set of silver-gray Pearls that fairly bristled with chrome pipes and mysterious fittings. That was a kit that invited heavy whacking.

Ken later picked up some lead vocals, too. The simple fact of additional voices added a welcome new dimension to the Turbines’ sound.

The Howling Turbines repertoire in November 1997. Ten of the 23 songs were new to the Turbines. Hubley Archives.

There was one other sonic supplement that is ridiculous to mention except for the fact that it had such a big effect. Actually, it was a big effect: a Danelectro “Daddy O” overdrive box that opened up a whole new world of noisemaking to me. I had been using a compressor for the big big sounds — and now the Daddy O enabled me to be not just loud, but abrasive!

But these Turbines really did howl.

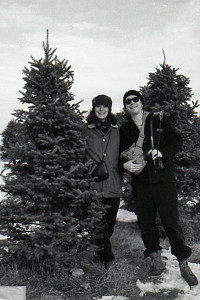

Another slice of the Turbines team. From left, photographer and longtime friend Jeff Stanton, Gretchen Schaefer, Ken Reynolds. Photo by Doug Hubley.

Early Howling Turbines rehearsal recordings on Bandcamp:

- Just a Word From You, Sir (Hubley) One of two songs I wrote for the Howling Turbines, this was an attempt to capitalize on what I perceived as our heavy-rock potential. Generally about my relationship with authority, it’s specifically about Stalin, Leonard Cohen and God. Go figure. A rehearsal recording from March 1998. Copyright © 2010 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.

- 1,000 Pounds of Rain (Hubley) The title was inspired by a 1990 Cowlix performance at the Drydock, for which — so as not to disturb the fried-clam scarfing multitudes — we had to carry the equipment to the second-story performance area up a cast-iron fire escape in a pouring rain. I lugged the title around for years not knowing what the song would be about. Finally finished in spring 1994, around the time the ‘Lix were splitting up, “1,000 Pounds” turned out to be a cry of despair at reaching middle age. This is one of a number of tunes that we carried over from the Boarders to the Turbines. A rehearsal recording from June 1, 1997. Copyright © 1995 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.

- Shortwave Radio (Hubley) Leonard Cohen once told an interviewer something to the effect that performing “Bird on a Wire” reminded him of his duties somehow. “Shortwave Radio” plays a similar role for me. I started writing the lyrics in an art history class at USM in 1981, and finished the song up over a gin gimlet in my sister’s living room on a summer evening, Bob Newhart on the TV, volume muted. This stayed in the repertoire for more than 20 years, from the Fashion Jungle to the Boarders to the Turbines. A rehearsal recording from May 1998. Copyright © 1982 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.

- Groping for the Perfect Song (Hubley) Like “Shortwave Radio,” “Why This Passion” and others, this early Fashion Jungle number seemed primed for a comeback when drummer Ken Reynolds rejoined bassist Gretchen Schaefer and me to form the Turbines. In this rough rehearsal recording I manage to goof up some lyrics including the signature opening line (hence the discount on this track on the Bandcamp store). I derived some sort of early inspiration for this from David Byrne, but that didn’t last. A rehearsal recording from March 1998. Copyright © 1983 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.

- Matty Groves (Traditional) Howling Turbines bassist Gretchen Schaefer and I devoted one of our first through-harmony efforts to this very old British folk song. It’s such a country tune! The success of this early HT staple encouraged us to try a few other folk songs like “John Riley” and “Pretty Polly,” but this was always the best of the lot. A rehearsal recording from June 1, 1997.

Notes From a Basement text copyright © 2012–2014 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.

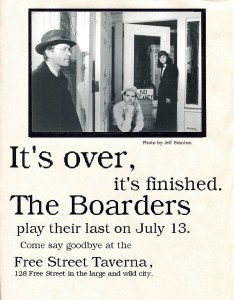

![Late in the 1860s novel Little Women, heroine Jo March, dreading her friend Laurie’s budding romantic feelings for her, tells her mother she feels “restless and anxious to be seeing, doing and learning more than I am.” Her solution is to move to the city, to live and work in a boardinghouse. There, she has a room to herself, time to write, and the welcome distraction of friendships with her fellow boarders. — Ruth Graham, The Boston Sunday Globe, Jan. 12, 2013 [Week of March 24] Boarders Let's begin with something deceptively obvious. Larger musical groups are empowered by their capacity for complexity. Smaller bands are empowered by the need to keep it simple. Obvious, for sure, but for the musicians involved, it's a powerful reality that encompasses infinite subtleties in both directions -- perhaps unexpectedly so in the case of the minimal. The richness of potential there can be highly gratifying. Every time I have gone from a larger to a smaller band, I've felt suddenly light, ready to fly. This was especially true in the case of the Boarders, the trio remaining after two musicians departed our so-called country band, the Cowlix. Singer Marcia Goldenberg left in March 1994 and violinist Melinda McCardell in May, after one last gig. My fellow remnants were Gretchen Schaefer, who played bass and guitar, and drummer Jonathan Nichols-Pethick. I played guitar and accordion, proposed much of the material and sang most of it. Post-Cowlix, we wasted little time finding a direction. And circularly enough, our direction was to be the Boarders. Atop a hard core of held-over Cowlix country and folk-dance repertoire, we added pop-rock by Buddy Holly, Jackson Browne and others. I was gratified to bring in two songs by Tim Hardin, one of my first big influences, to the repertoire. We learned two by the Kinks; the Oysterband's brilliant "When I'm Up"; Anne Savoy's adaptation of the Cajun song "Mon Chere Bebe Creole." From the torch song catalog came "What's New" and "I'll Be Seeing You." We glommed up enough Leonard Cohen to jokingly bill ourselves as Portland's only L.C. tribute band, even tackling the French Resistance anthem "The Partisan," which Lennie covered on his second album. And we revived several originals by my pre-Cowlix combo, the loudly romantic Fashion Jungle. Speaking of which, among other improvements that came with the Boarders, it was here that I felt at home as a songwriter again after five years adrift. It was ironic, or at least telling, that toward the end of the 'Lix I was thinking about revisiting Fashion Jungle material (and we even picked up "Shortwave Radio"). Apparently I am on a short chain fastened to a post in the ground, because I walk in one direction until the chain is wrapped completely around and then I wind it again the other way. In the four years of the Cowlix, I wrote two songs: "Slow Poison" and "Trouble Train." In the two years of the Boarders, I wrote three, including two that I consider among my best, "1,000 Pounds of Rain" and "Watching You Go." And for the first time since the Fashion Jungle, I wasn't the only songwriter in the band. We hung onto Jonathan's "All Over," and he and his wife, Nancy Nichols-Pethick later presented "Tragedy." Nostalgia wears rose-colored contact lenses, but it seems to me that our musical interests were as harmonious as everything else about the Boarders. I don't recall Gretchen, Jonathan and me ever discussing our repertoire in broad or aspirational terms, and neither did we disagree about material. We just brought songs in and, for the most part, played them. It was a relief to lose the country music fiction espoused by the Cowlix, a band with a long stylistic reach and a grasp that almost matched. As previously noted, I, at least, had started violating the "country" descriptor early on. And now here were the Boarders with no such mandate to obey or defy. Like the Cowlix, we had the range to pull off a variety of music, but there was a crucial difference: What the 'Lix lacked and the Boarders possessed was a collective personality focused enough to forge an identifiable sound from some disparate types of music. Much of that personality was purely musical and organic, but -- and I know it will shock and surprise you that such things happen in the music biz -- some slight contrivance went into the Boarders' public identity. The three of us had zero interest in retaining the Cowlix name. Not only did we wish to leave the past in the past (as I am obviously so dedicated to doing), but we had discovered along the way that we weren't the only ones using that name. Pretty obvious moniker for a country band, after all. I don't recall where or how "Boarders" turned up, but it seemed sufficiently random-yet-meaningful, that irresistible combination, to work for this "new" band that seemed capable of anything. The richness of the Boarders' prospects and potential, coupled with my decade-plus experience, as a music journalist, with musicians angling for my attention, prompted a fairly focused publicity campaign. We even created press kits, including a band history (remarkably free of factual content), demo tapes, a sample lyric ("Trouble Train"), publicity photos by longtime friend Jeff Stanton -- and a key pin. Key pin? Just like it sounded: an old-fashioned lever-lock key with a pin-back epoxied onto it, so it could be worn as a pin. The key concept was derived from the boardinghouse concept, and the whole works was derived from my realization that journalists and club owners would be more likely to remember a band that gave them presents. Who doesn't like presents? I have no idea whether the key pins made any difference to our getting work -- although we did get work. But, revisiting the two key pins that I still have from that exciting Boarders efflorescence 20 years ago, I would like to think there are still a few Boarders key pins turning up, from time to time, on the sport jacket lapels and cloche hats of Portland's hip-and-cool.](https://www.dhubley.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Boarders-JS-LEDE-1024x680.jpg)