Interlude: 10 Million Papers

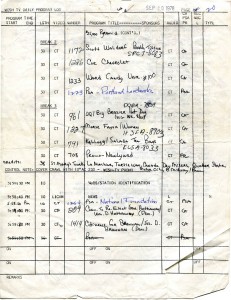

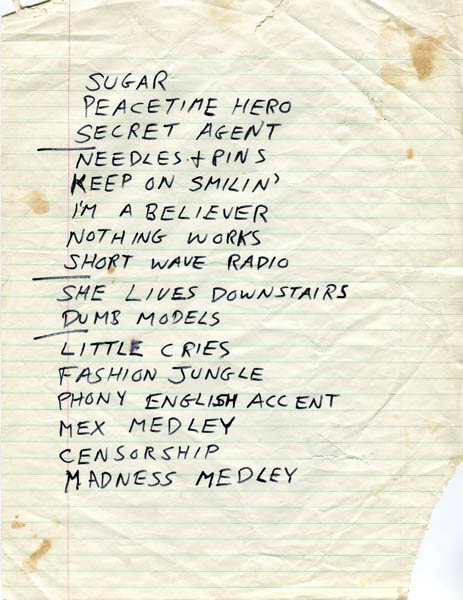

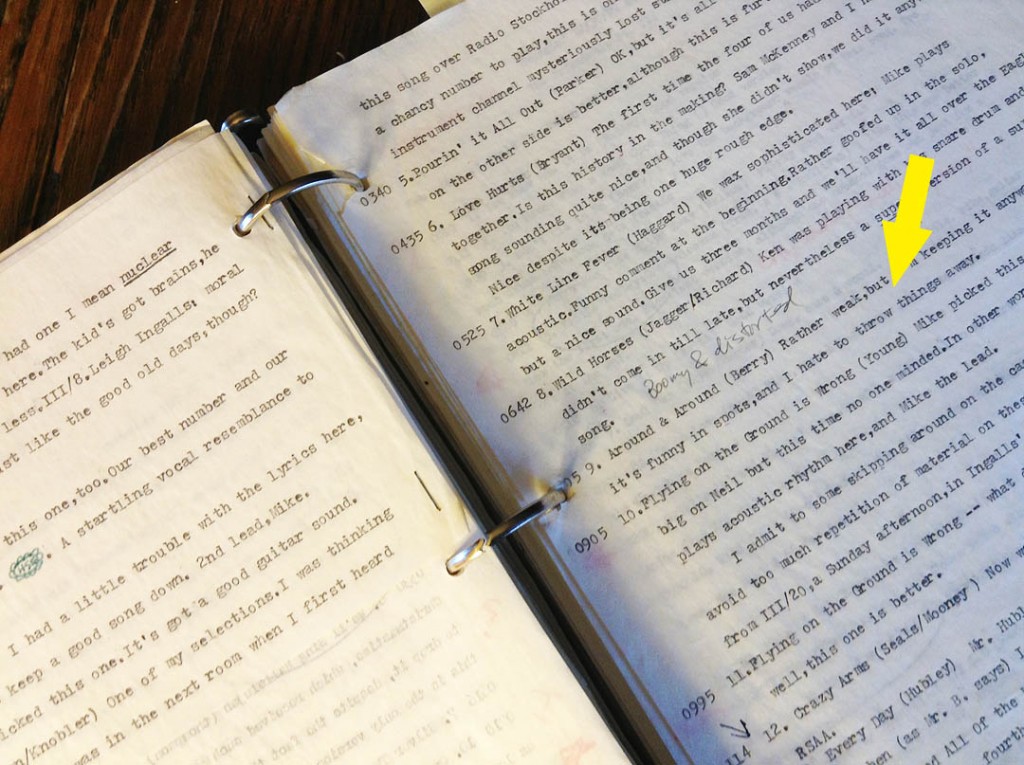

Track listings for two reel-to-reel recordings by the Curley Howard Band in my Tape Catalogue. The comment indicated by the arrow sums up this entire post; click to embiggen.

See a mind-bending collection of items from the Hubley Archives. And it’s only the tip of the iceberg!

A break from the band chronology, with an overdose of materials from the archives:

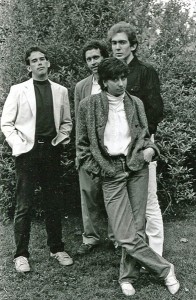

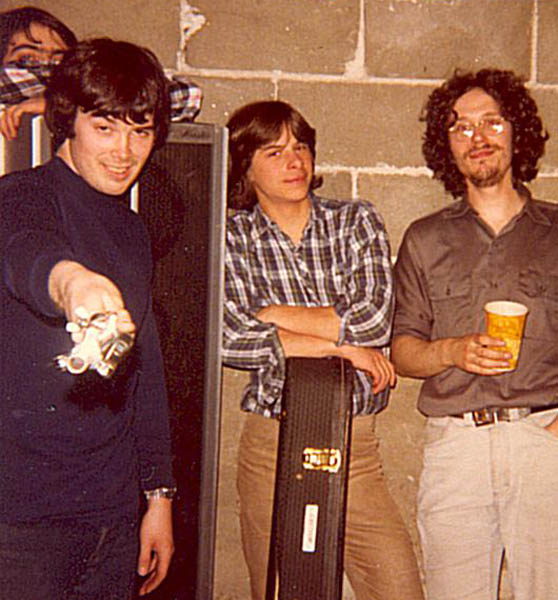

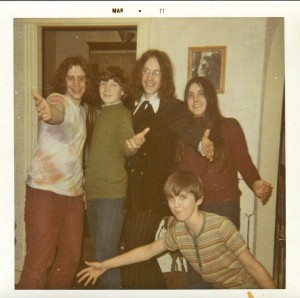

This Kodak Instamatic (not Instagram, Instamatic!) image from winter 1971 shows three of the four members of my first performing band, Truck Farm, which came together later that year. Clockwise from left: Tom Hansen, drummer; John Rolfe, guitarist; DH, dolled up for who knows what; and our friends Patty Stanton and Scott Stanton. Hubley Family photograph.

When you see people close to you losing their memories, and your own is less than rock-solid, it may cause you to think seriously about what you remember. And what it means: the role memories play in your thinking and in your understanding of your life. The ways you call memories up, examine them and try to hold onto them. The fact that they are so plastic, and ultimately fugitive.

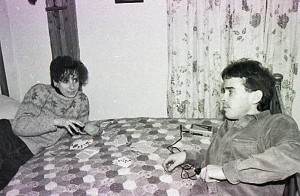

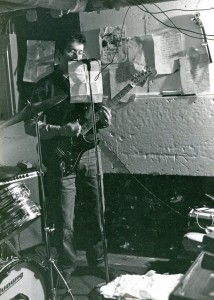

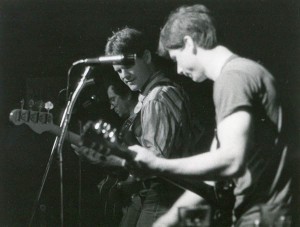

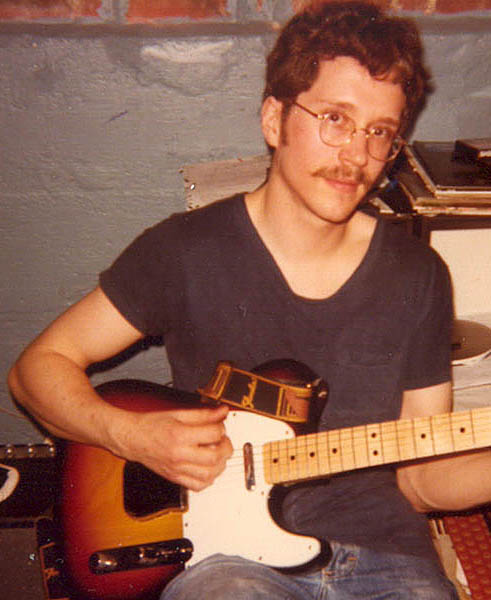

A South Portland police officer pays a visit to an early Truck Farm rehearsal en plein air at Craig Johnson’s house. I still hear him saying, “Can you tone it down a little bit, boys?” I’m at right and Tom Hansen at left in this image by an unknown photographer from spring or summer 1971. Hubley Archives.

Are we merely the sum of our memories? Do they accrete onto the bare armature of our personalities like layers of clay? Can you do anything with your conscious mind that isn’t somehow connected with memory?

Are memories a form of currency in the social marketplace — that is, if you remember more, are you a more interesting person? Do you have a mental wallet or portfolio of stories about yourself that you whip out at appropriate moments in a gathering? (I am generally barren of amusing stories suitable for social occasions, although there is the one about the dress shop in Vienna.)

How is it you can not see somebody for two years, and then when you meet again, you pick up the conversation like it was just yesterday?

Why are memories of life experiences — the stories that seem to constitute our lives — so important to some people, like me, and not others?

See a gallery of Truck Farm Images. Text continues after gallery!

See the Archives page, offering way too much information.

Dating myself

I had a great memory, with a particular facility for dates, into my 40s. I had a reputation for my ability to recall the dates when things happened, even fairly unimportant things. Example: On Oct. 24, 1970, my mother took Tom Hansen and me to see Poco at the University of Maine Portland-Gorham.

My sticky memory was one of the primary colors of my sense of self. Now it’s fading, not drastically, but noticeably. As with the other things that age has diminished, I accept it, because what else can you do? But it dulls my self-esteem and leaves a numb spot in my mood, like the flat place on your gums where a tooth used to be.

At worst, it worries me that it’s the start of some kind of serious deterioration. But I try not to go there too often.

The documents in the case

I’ve always associated memories with documentation. For me, a piece of paper or a recording is like a ticket to something I experienced. It’s hard to say which came first, this belief or my paper-saving habit, but I’ve amassed a lot — lyric sheets, newspaper clippings and night club listings, set lists, photographs, performance and rehearsal recordings, letters, journal entries (way too few of those), etc. And that’s just the stuff related to music.

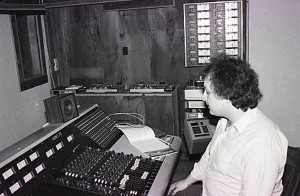

One of the most robust sources for these strolls down Memory Lane is the “Tape Catalogue,” my extremely annotated index of most of the analog audio tapes that I own, about 130 reel-to-reel tapes and god knows how many cassettes. These are life experiences of a especially vivid kind that are embedded in physical objects, and for the most part, the objects are unique. You can copy an analog recording, but always with a loss of quality, vs. a digital recording, which is endlessly replicable with no loss of quality (except the upfront loss of quality inherent to digital recording).

That replicability is one reason digital audio media are disorienting to a product, like me, of the analog age. A slightly different reason has to do with physicality. Digital recordings ultimately exist as physical media, of course — on a server somewhere — but you don’t need to have them in your house to access them, and you don’t have to own them to access them.

How unsettling. I am all about owning things and having them in my house. Can you really get anything from a Cloud besides vapor, rain or snow? But ultimately all our endeavors, and their physical manifestations, will evaporate anyway, no?

Tickets, please

I’ve always believed that by revisiting the document, the experience will somehow spring back to life fully formed in my mind.

In the nine months I’ve been writing these posts, though, the mnemonic payoff from all the paperwork hasn’t been quite so dramatic. It has been nice to rediscover the facts in the documents, but the big payoff — the once forgotten, now recalled scene in the Movie of Doug — has rarely been forthcoming.

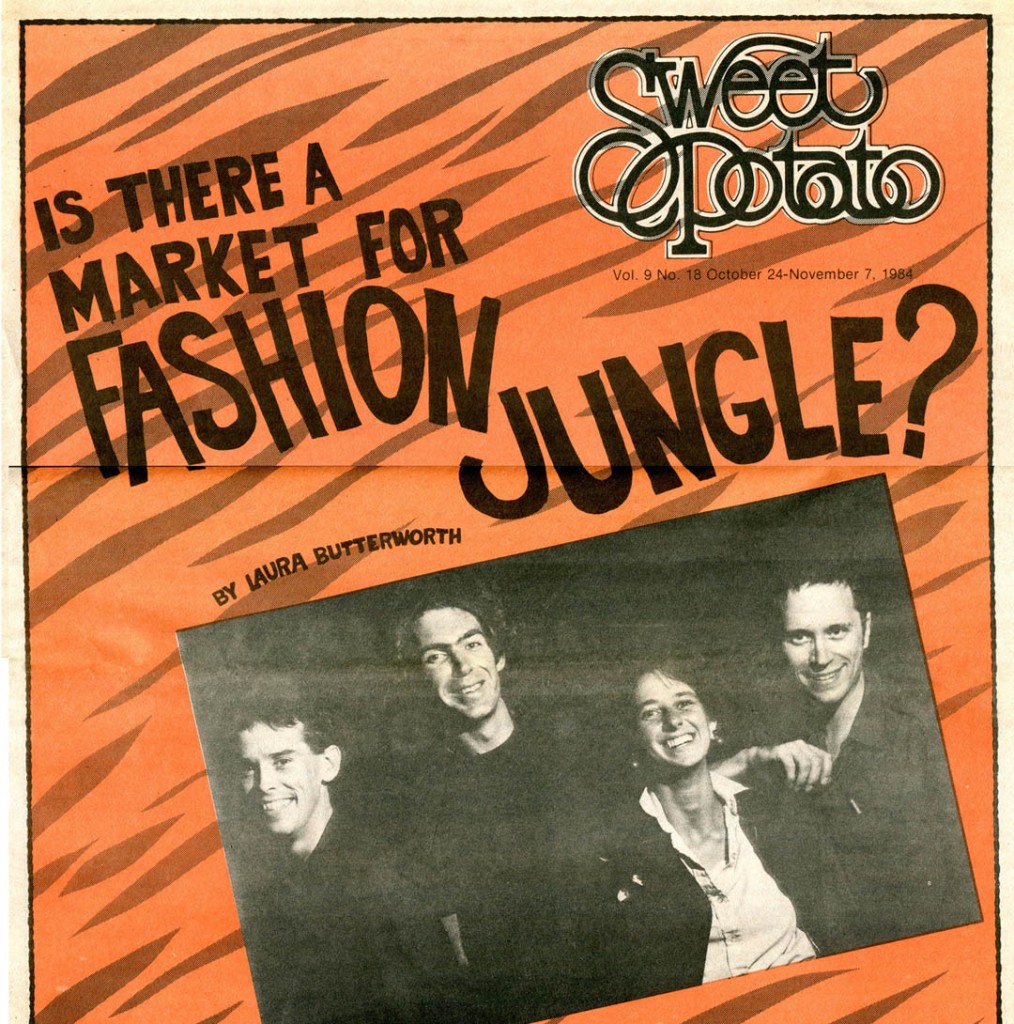

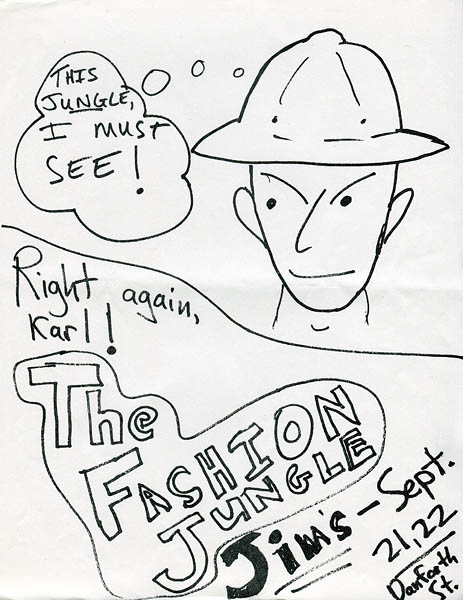

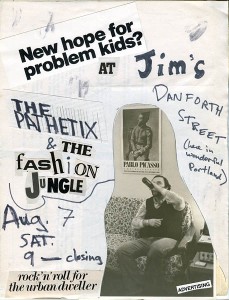

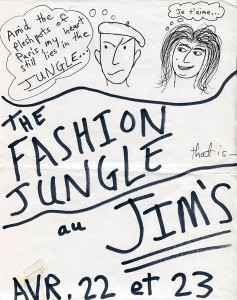

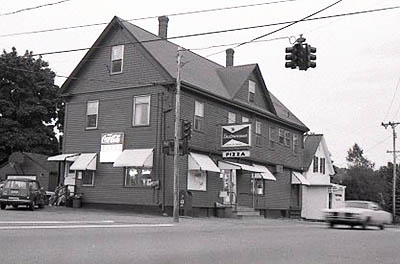

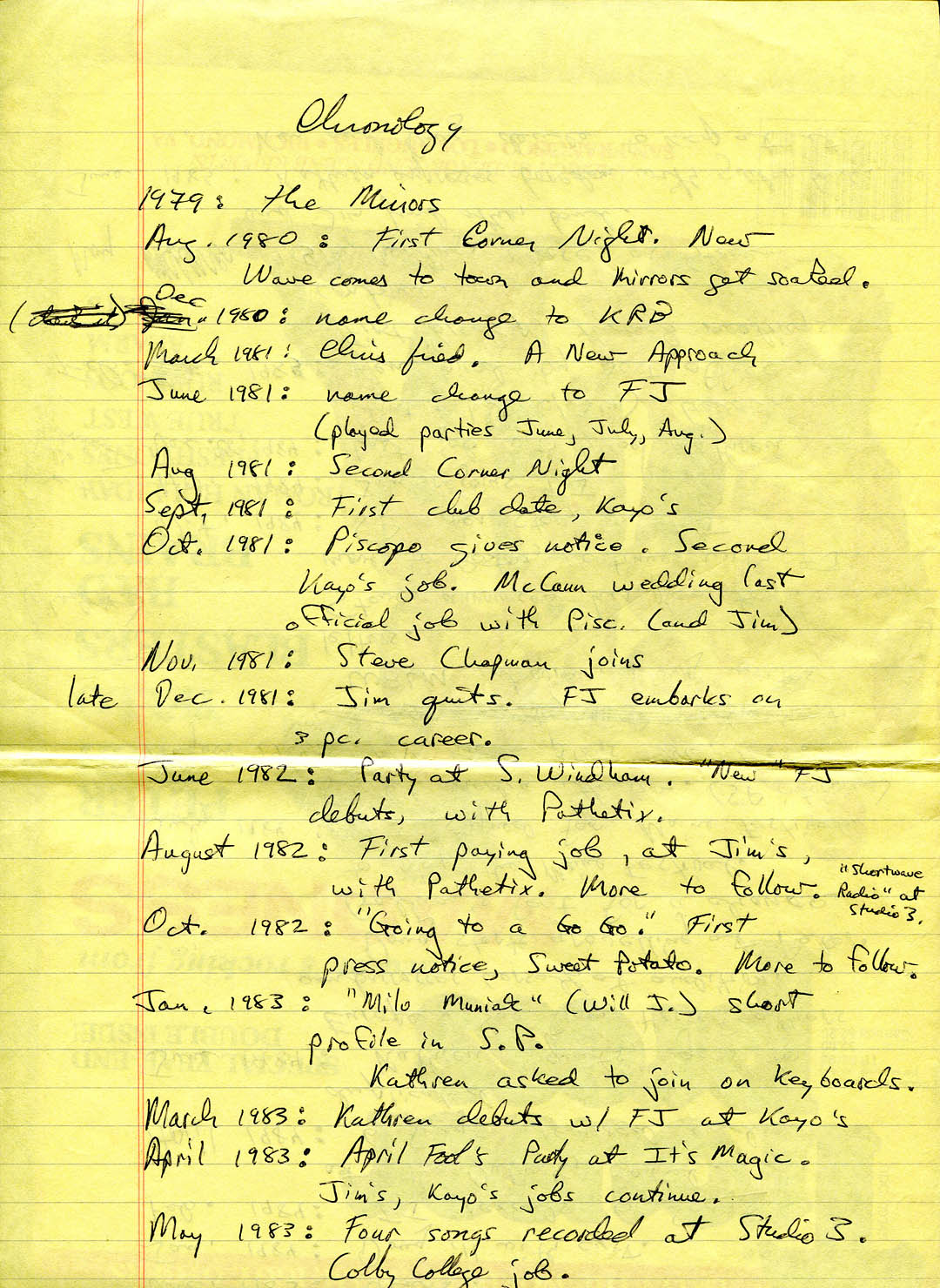

A page for a chronology of my bands that I drew up in preparation for a never-completed 1985 slideshow about the rise and fall of the Fashion Jungle. Note the March 1983 entry. Hubley Archives.

So documentation isn’t the key to a lockbox full of precious memories. There’s not always even an exact correspondence between one paper item and one recollection. The best I can hope for is random and fragmentary recovery of memories from the abyss.

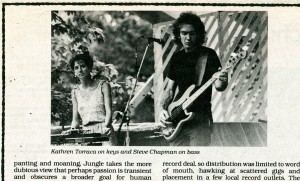

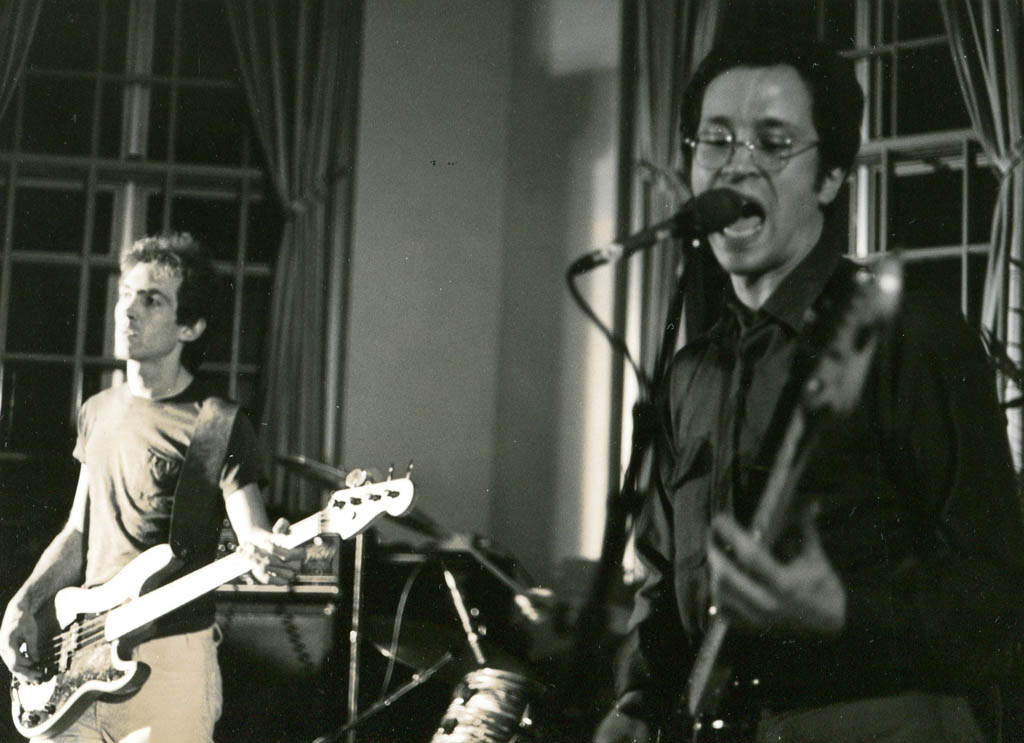

For instance, this autumn I was surprised to be reminded that the Chapman-Torraca edition of the Fashion Jungle stayed together (to the extent we could, with members living in Boston) until March 1985. This intelligence came from a handwritten band chronology that I started back in the 1980s, when I was really manic about documentation, and that I just unearthed.

From a hasty logbook of Fashion Jungle operations that I kept in 1983, I was able to disabuse myself of the erroneous belief that Kathren Torraca’s FJ debut was at a certain club on a certain date and relearn that it was at a different club, good old Kayo’s, on an earlier date. The big takeaway there was not so much the facts of her debut, but the realization that I’d remembered them wrong all these years, just because I had a tape of one gig, her second with the FJ, and not of her first.

The documents give and the documents take away.

See the logbook and other Fashion Jungle images. After visiting the second gallery installment, use the back arrow to assure the optimum Notes From a Basement experience. Text continues after gallery!

See the Archives page, offering way too much information.

The rehearsal lyric sheet for “Shortwave Radio,” typed on my blue Smith-Corona portable. The yellow splotches on the paper are probably sweat or Freixenet sparkling wine, which I drank constantly during the golden summer of 1981.

Incidentals

Song lyric sheets are quite evocative. They, more than any other category of the rubbish I hoard, often return me to the day. As I’ve previously written in this space, one of the clearer memories I have from the original Fashion Jungle days in 1981 is the writing of “Shortwave Radio” — sitting at the red table in my sister’s house on Cottage Road, drinking a gin gimlet, “Bob Newhart” rerun on TV with the sound off, etc. My process is to scribble down a bunch of crap until it coalesces into a song, and when it seems solid enough to start on the melody, I’ll type a clean copy. But the “Shortwave Radio” lyrics here give me a change to talk about secondary, but still alluring, aspect of documentation: incidentals.

Nicholson Baker, an unusually focused writer whom I interviewed in 2000 following his purchase of the British Library’s hard-copy newspaper archives, first opened my eyes to the historical power of incidentals. He wrote (in The New Yorker, I think) about the computer databases replacing physical card catalogs in libraries. He didn’t like it; and one reason was that librarians tended to mark up catalog cards, and their markings constituted an important source of information that would be lost with computerization.

That made perfect sense to me. Nothing happens in isolation, and the bits of stray information that come along with what you really intended to save can shed light on the context in which the primary event took place.

In this spirit, I’m presenting not only my original master copy of the “Shortwave” lyrics, but the backside of the paper I typed them on. It was originally the front: My father, Ben, worked in advertising sales at WCSH-TV, and being obsessively thrifty, would bring home discarded program logs (showing information about commercials) for use as scrap paper.

Ben and Hattie still have in their den the pale green desk that was the repository of writing materials at 103 Richland St., and there’s probably still a pile of these log sheets in with the scrap paper in that desk. (Although the last time I went looking there for scrap paper, I latched onto a hunk of continuous computer-printer paper, the kind with the detachable sprocket holes, and it just kept coming, sheet after sheet. That was two days ago.)

So, after you read the lyrics to “Shortwave Radio” and then go to my Bandcamp Store to buy a copy (and then I would request that you burn it onto a CD and then copy it to an audiocassette, all while thinking of me), take a look at the entries on the program log. When was the last time you saw a TV ad for Canada Dry mixers or Quaker State motor oil? And note the political spots at the bottom of the sheet.

See more original Fashion Jungle images. Text continues after gallery!

See the Archives page, offering way too much information.

This is it

It strains me to have to accept that my legendary memory ain’t what it used to be. Time is hollowing out the past as it exists in my mind. It shakes me up to have to acknowledge this.

But acknowledge it I must. I know people much older than me who share my belief (or more likely gave it to me) in the evocative power of documentation, and I’ve seen how the memories continue to evaporate while the goddamned paperwork just keeps piling up like the snowdrifts in the pre-climate-change winters that we don’t have anymore. Paper covers rock, but it doesn’t stand a chance against time. And neither do the rocks.

The saddest or silliest thing about all this musing about documents and memories, about the paper trail that leads to an outline of a version of a possible life, out of all the possible lives, is that for all these years I have entertained the notion that all these documents would someday be of historical interest — that I should keep them because some institution would someday want them for the sake of researchers who would want to know more about me. This on the basis of a small writing career largely given over to the exercise of marketing communications; and a tiny musical career.

It embarrasses me to confess this, but I do so in the hope that it may (a) be of some kind of interest — delusions being both entertaining and informative — and (b), more selfishly, that it might help me get over the idea.

I’ve come to realize that if anyone’s going to write about me, it’s probably going to be me. And I’m already doing it. And thank you for continuing to read it.

As long as we’re rummaging around in the archives, here are four more recordings for your pleasure and bemusement.

- Nothing Can Change the Way I Feel (Hubley) A song written in 1978 as an exercise in self-directed propaganda. Even then I knew the relationship was a mistake. The words are clunky — does metallurgy really have a place in tender romantic lyrics? — but the melody is nice. (Gene Clark much?):

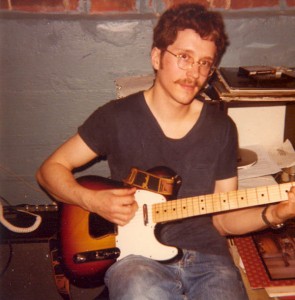

- What You Wanted (Hubley) Three-quarters of the Fashion Jungle perform this sort-of love song in the Hubleys’ basement in September 1983. DH, guitar and vocal; Steve Chapman, bass; Kathren Torraca, keyboards. Drummer Ken Reynolds was on the disabled list with a thumb broken playing ball, so the percussion is electronic. This was from a recording session dedicated to preserving our material for a new keyboardist, because Kathren was threatening to quit. (She didn’t.):

- Why This Passion (Hubley) An early version of a romantic song debuted by the FJ in 1984. In later years, this cumbersome setting was discarded for a more straightforward and rocking arrangement. Recorded at Geno’s, Oct. 12, 1984:

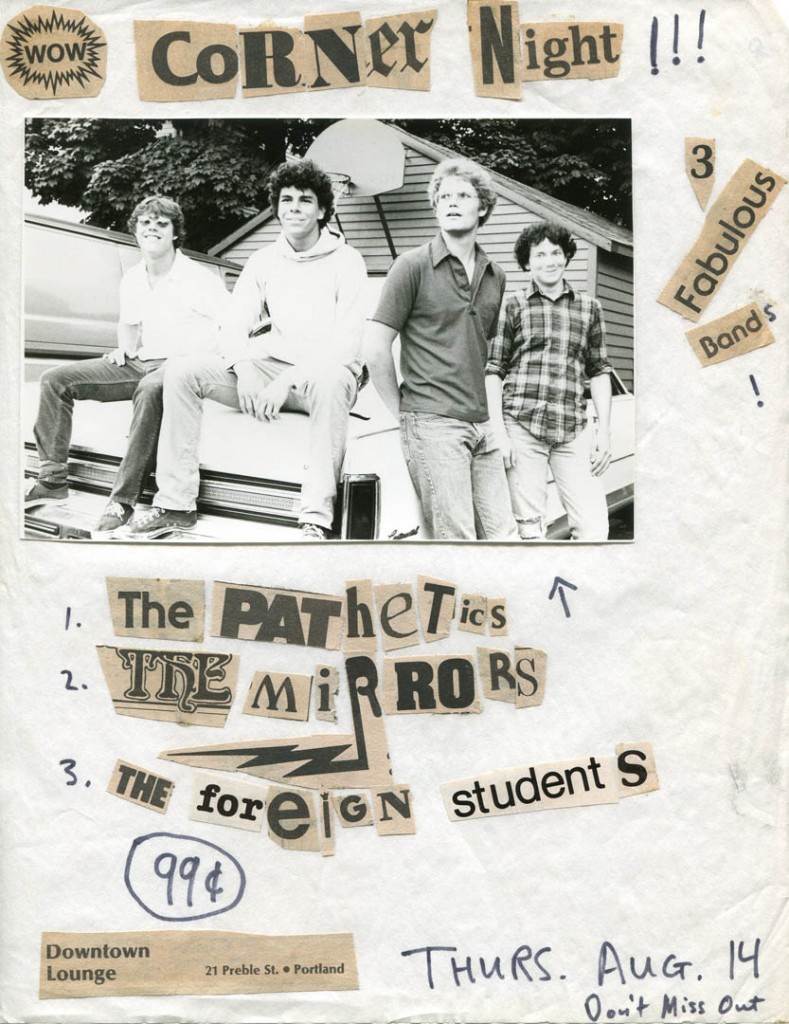

- Corner Night (Demo 1985) (Hubley) Elvis Costello much? Ray Davies much? Self-referential much? I wax reminiscent about the early days of the Fashion Jungle in this song written and demoed in 1985 for the Dan Knight edition of the FJ.

These four songs copyright © 2010 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.

Text copyright © 2012 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.

See images from the times before and between bands.

See the Archives page, offering way too much information.