From a Hole in the Ground, Part One

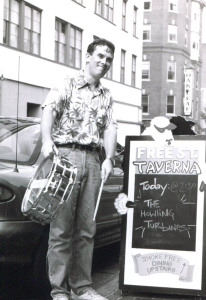

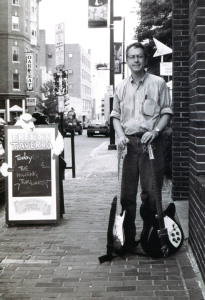

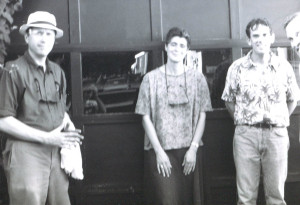

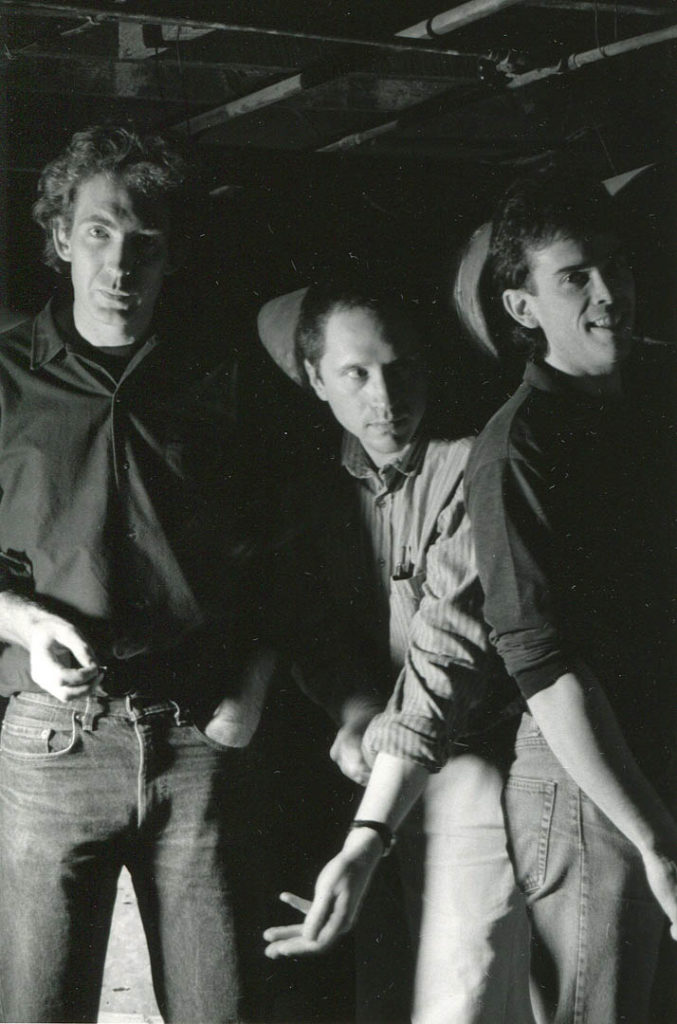

The Fashion Jungle rehearses in Ben & Harriette Hubley’s basement in a composite image from the early 1980s. From left, Steve Chapman, Ken Reynolds, Doug Hubley. Photos by Jeff Stanton.

See the basements, read about the basements — and hear the basements in the Bandcamp store!

NOTE: All musical excerpts in this post were recorded in basements except the first one, which I included so that you can hear the Kent guitar and Capt. Distortion amplifier, played by Steve McKinney; my bass playing heard through the RCA stereo; and Tom Hansen playing cardboard boxes, a tambourine and a metal bicycle basket as percussion. We all sing, and Judy McKinney sings and plays rhythm guitar. This was recorded in the Hubleys’ living room in 1969.

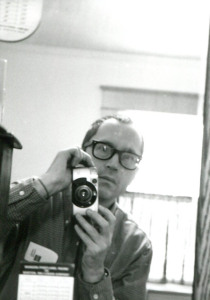

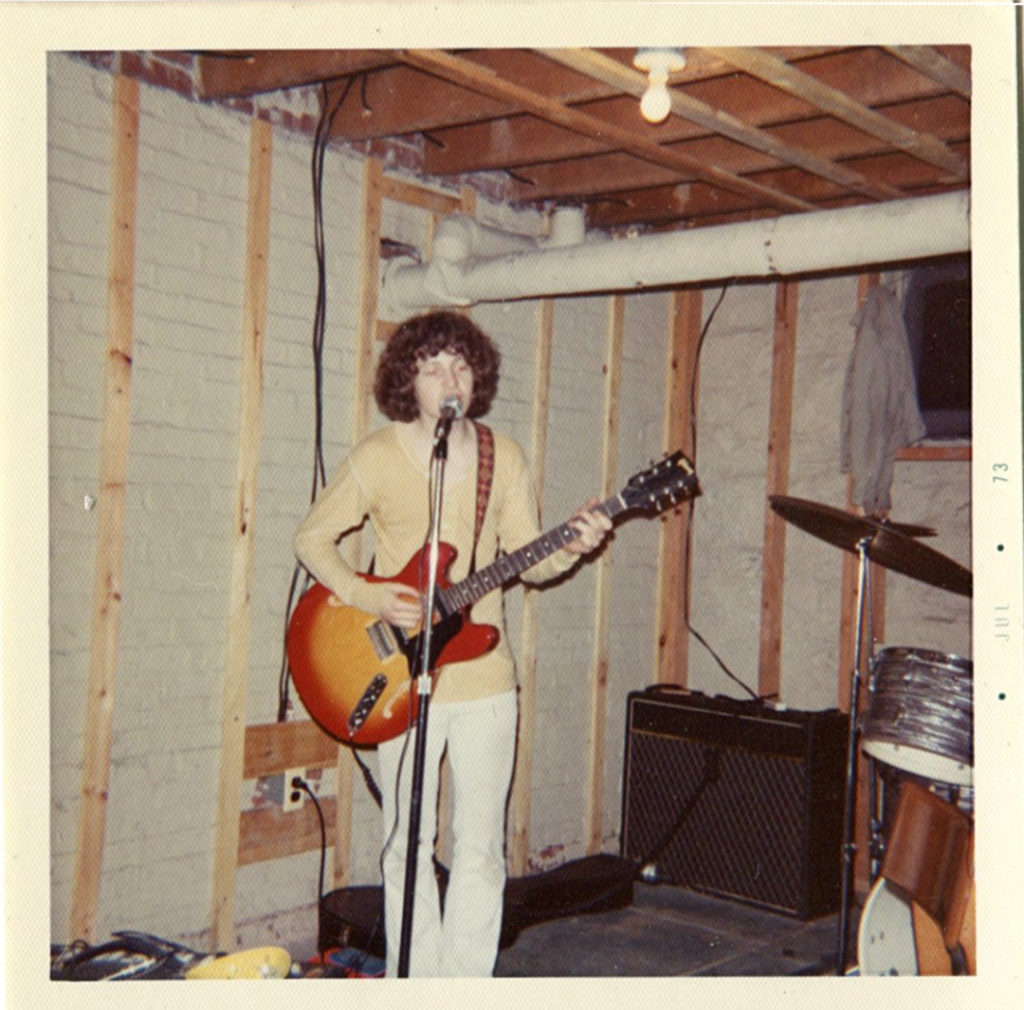

My parents’ basement in South Portland, Maine, in the late 1960s. Notice the particle board stereo speakers, the coffee-can light fixture at upper left and the cloth speaker grille on Capt. Distortion, lower left. This image is the source for the Notes From a Basement banner. Hubley Archives.

Most musicians from Bob Dylan on down,

especially those of a certain age, can tell you about making music in a basement.

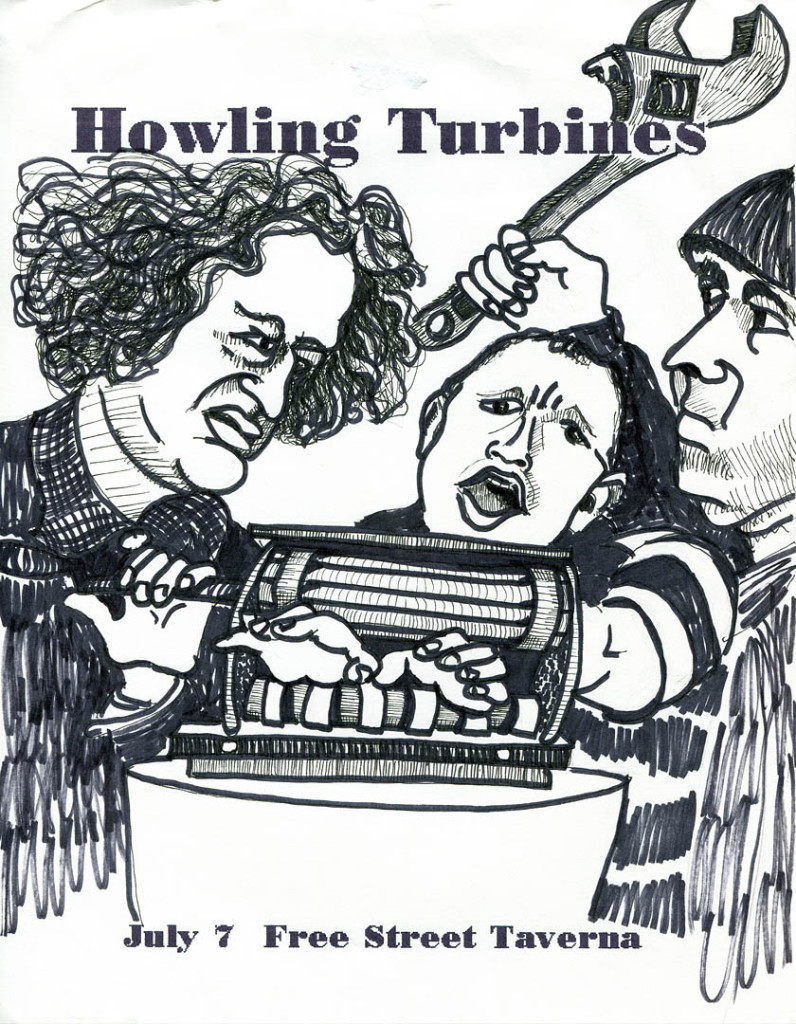

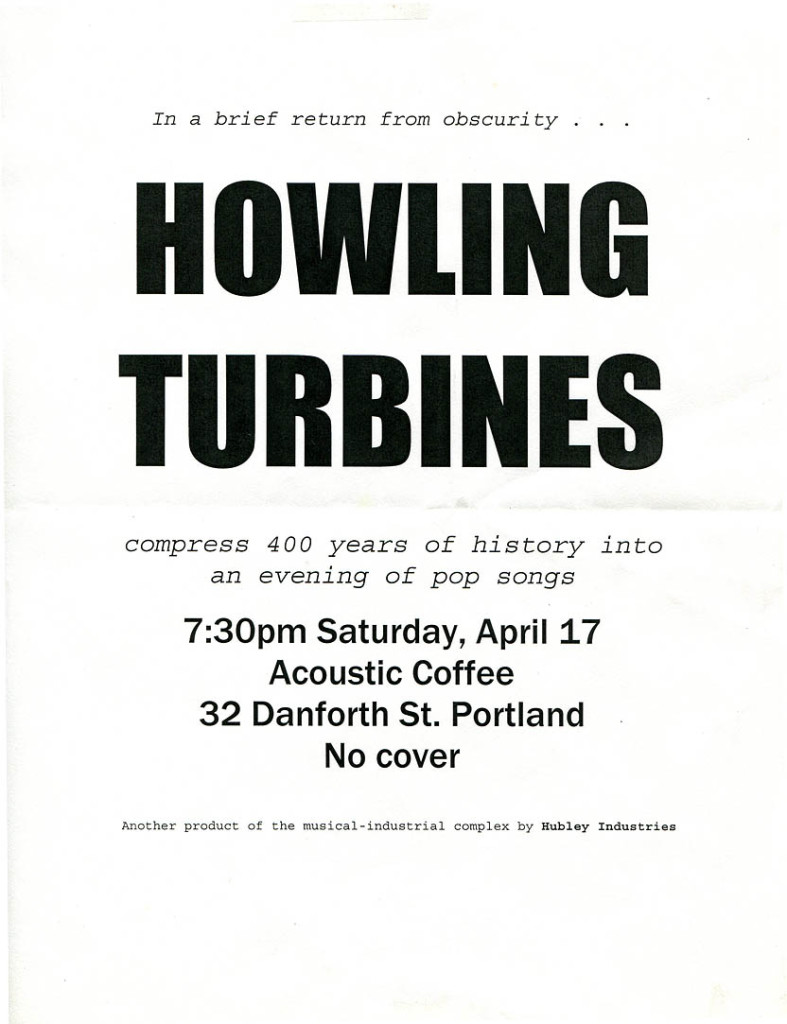

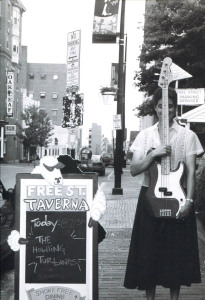

I count at least nine residential basements in which I’ve played alone or with bands — to say nothing of such illustrious subterranean nightspots in Portland, Maine, as the original Geno’s, Squire Morgan’s, the short-lived Ratskellar and the Free Street Taverna (only slightly below street level, but with a true basement feel).

An equivalent view in April 2013, after we cleared out the house for sale and my parents moved into assisted living. Hubley Archives.

Allow me to explain the obvious. Musical equipment takes up a lot of space, is hard to dust and to vacuum around, and looks good only in its functional context — that is, when you’re using it to play music or make other musicians envious.

In addition, of course, electric music can get loud. And by the same token, domestic life can interfere with musical moods. You don’t want someone watching NASCAR nearby when you’re trying to record a tender folk ballad.

Perhaps most decisively, musicians at work create a powerful social energy that, for better or worse, intrudes into whatever hopes for their time your non-musical roommates might be aspiring to.

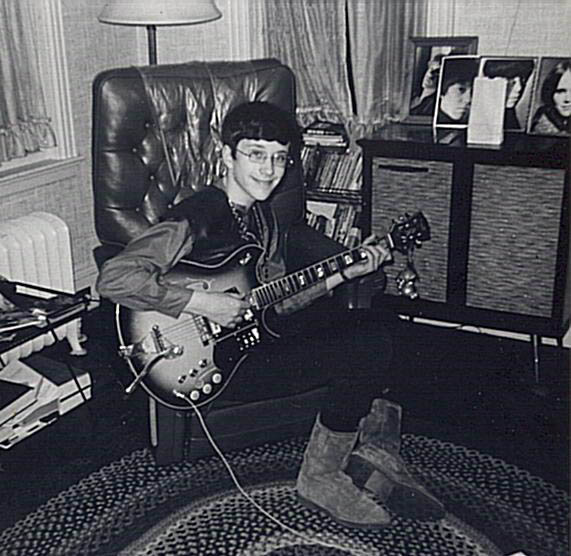

Me and the Kent, my first guitar that I didn’t steal from my sister. Pre-Capt. Distortion, it was plugged into the RCA Victor stereo. Hubley Archives.

So for many of us, music gets made in the basement — spiders and pill bugs, dust and grit, mildew and mold, darkness and chilliness be damned. (Garages, of course, also have a noble history as musical refuges, even lending their name to a musical genre).

And don’t forget the water during snowmelt and heavy rains. Standing water on the basement floor every spring was a special attraction in the 1910 house where I grew up, on a side street near Red Bolling’s legendary Tastee Freez (now known as Red’s).

When we moved in, in 1958, the largest of the three cellar rooms was set off by a pair of French doors. If a 60-year-recollection is worth anything, that space briefly harbored a little sitting area with curtains and some kind of dainty furniture. (I’m the only Hubley who remembers that amenity. Dream or reality?)

One French door, with all of its glass but painted into opacity, still remained 55 years later when we cleared the house out and moved my parents into assisted living.

The massive gray gizmo on the green hassock was a “portable” turntable, weighing about 40 pounds, that once used by WCSH-AM for remote broadcasts (if that’s still a recognizable concept). Hubley Archives.

Anyhoo, back there in 1966 or ’67, one or both of my sisters, who are older than me, turned that room into a hangout. They walled half of it off with blankets, and added amenities such as an old, deep stuffed chair with a rock-hard seat and touches of paint that included “I love you” (and, less idealistically, “69”) daubed on the bricks.

As my sisters’ hangout-related interests matured and my involvement in music deepened, I claimed the room. But it didn’t happen overnight. What shaped the situation was a chronic inadequacy of musical gear that prevailed until I was out of high school and drawing a paycheck. (I’m often gobsmacked by how well-equipped today’s young players are.)

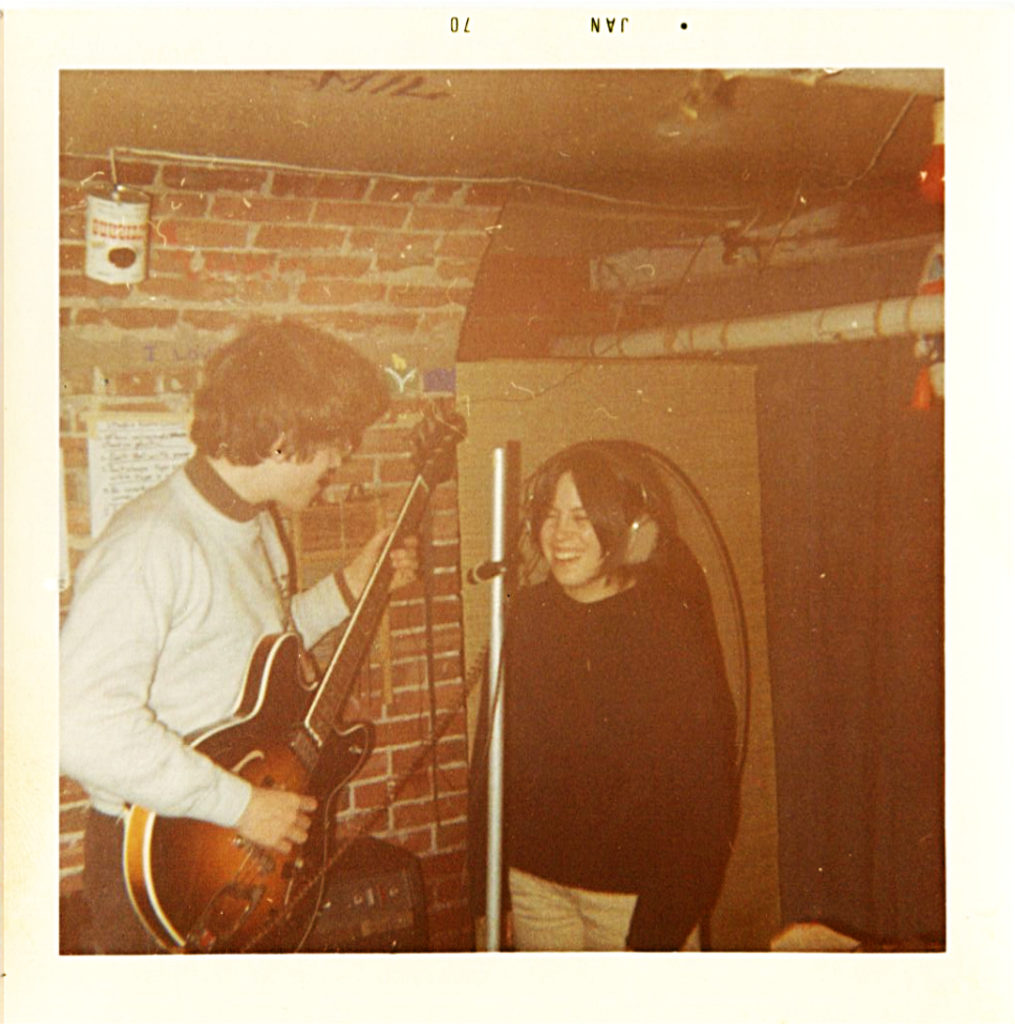

Doug plays bass through the new Guild Superstar and sister Sue Hubley sings in early 1970. The “mic stand” was a tent pole. Hubley Archives.

During those 30 months before I got the Guild Superstar, my father improvised a couple of solutions to my unamplified plight. (Dad knew electronics — he’d even been a radioman with Eisenhower’s headquarters during WW II.)

First he rigged an input to the household record player, a much-modified RCA console model in the living room. The Kent sounded clean through the RCA — a bass sounded better, as it turned out — but the disruption to the household was significant.

Dad’s next offering was a bare-chassis amplifier of unknown origin (record player? intercom? public-address?) hooked up to an 8-inch speaker that must have come from some other console record player. The speaker was mounted onto a cloth-and-wood panel, and the amp was screwed onto a plain pine board. Dangling wires connected them, and the whole works teetered on a rolling metal TV stand.

It wasn’t too loud but it sure sounded rough. In fact, it set a standard of overdriven amp tone that remains a criterion for me, in a good way. I called that contraption Capt. Distortion.

I continued to clear the living room with the RCA from time to time, but the Captain really changed my musical life. Most importantly, the Captain — along with other stopgaps, such as a second-hand particle-board stereo that Dad also dredged up from who knows where — untethered me from the living room.

And, actually, tethered me instead to basements.

Cellar, beware

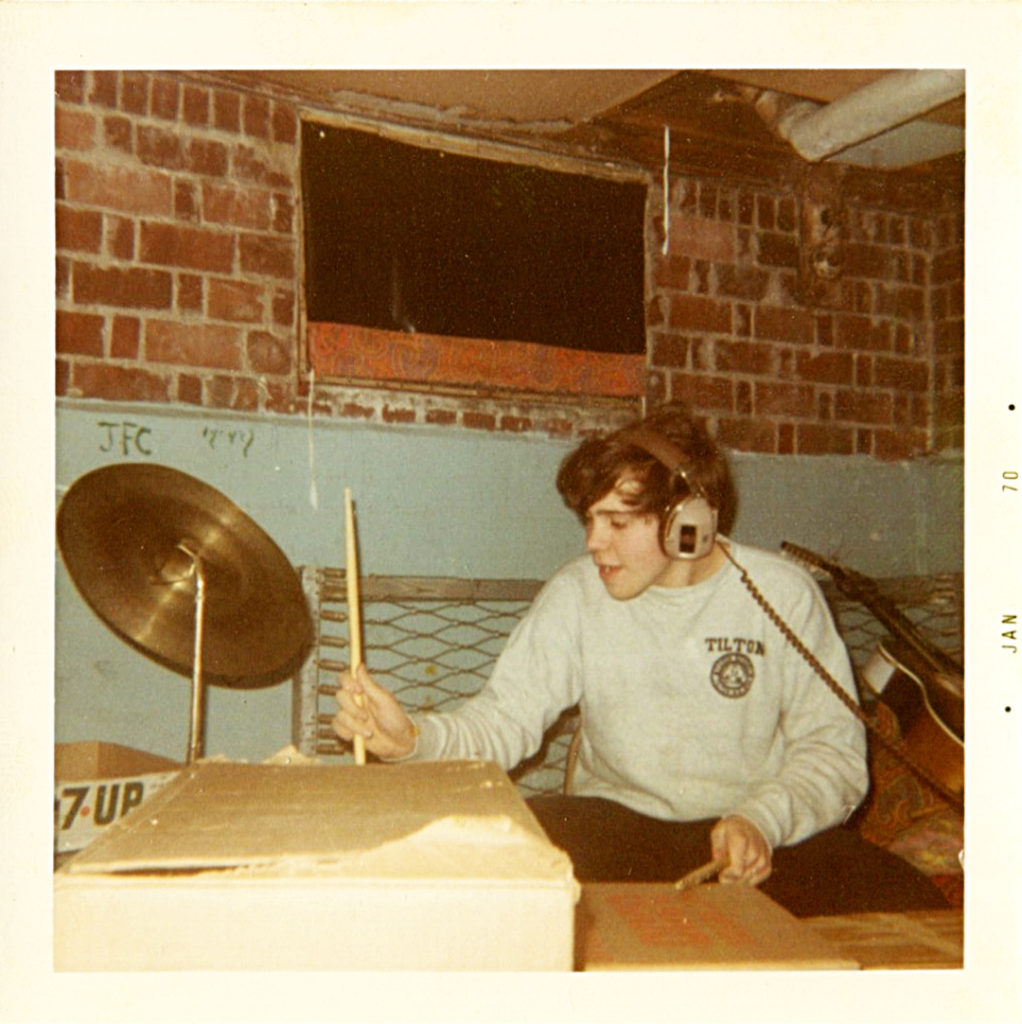

Drummer Tom plays cardboard boxes and a real, though cracked, cymbal, in the Hubley basement in early 1970. Hubley Archives.

Our adolescent energies converged like phaser beams on my father’s poor Panasonic reel-to-reel tape recorder. We used it, with a succession of cheap plastic microphones, to record music ranging from earnest and bad to cacophonous and unlistenable. We also attempted comedy. Tom and I spent most of 1969 and ’70 recording crap on that poor tape recorder.

To the basement decor I added some colored light bulbs (I still remember buying them. I still have a green one), and Tom and I sat there in the near darkness just killing ourselves with what we considered really funny stuff. It’s just amazing how wrong people can be.

John Rolfe rehearses with our band Airmobile in the basement of a building at what is now Southern Maine Community College. This was summer 1973, the school was then known as Southern Maine Vocational-Technical Institute, and the building was the residence of bassist Glen Tracy, whose father worked at the college. Hubley Archives.

The Thunderbirds (previously Airmobile. It gets confusing) are back in the Hubley basement in this image from 1974. At left is bassist Glen Tracy. The drummer is Eddie Greco. Hubley Archives.

Despite a few recurring bits, we pretty much winged each episode, exploring every corner of offensive adolescent spontaneity we could find. Between making music and “Captain Spoon,” we felt pretty special, which the thugs at South Portland High School rewarded with accusations, which sometimes escalated into physical harassment, of being gay. An enlightened era.

Tom and I remained friends through the SPHS grief and through his parents shipping him off briefly to private school to get him away from me. (Despite their fears, there was no gay sex, no booze, no drugs; just colored lights, stupid humor, music that gradually got better and an abused tape recorder). What did end Tom’s and my friendship was starting a band when we were 17. And, of course, becoming mature.

The Hubley studio post-paint job, 1974. Hubley Archives.

Years of a basement

Where most of my contemporaries in the early 1970s were absorbing the influences of school, sports, clubs, church and who knows what all, my character was being molded by records, radio, Rolling Stone and Hit Parader magazines — and my parents’ cellar.

The Hubley basement studio at its apogee, in the mid-1970s. Note the Chevy hubcap ash tray, the three tambourines hanging from a beam, and the Carmencita psychedelic guitar at right. Hubley Archives.

A few years later — I was 20 and really should have known better — I pretended it was a nightclub and invited cronies down for drinks and performances. Friends knew to bypass the regular house entrance and come in through the cellar door, which was reminiscent of a bomb shelter entryway.

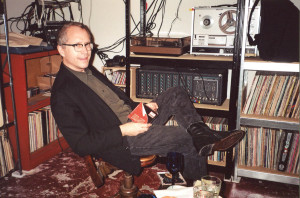

Ensconced in the ass-numbing maroon easy chair, Ken Reynolds appreciates the Hubley cellar in 1977. Hubley Archives.

The standard of furnishings rose slightly, as I replaced old Hubley discards with newer ones. Gone was the old mattress and frame that served more to mock than to make possible any possibilities of l’amour. In addition to the original ass-numbing stuffed chair, there was a car bench seat (later replaced by the old pink family sofa) and a giant hassock covered in limeade-green fabric. There was a Chevy hubcap for an ashtray, although nobody much was smoking.

More important, the standard of musical furnishings rose markedly. Thanks to real jobs, first at the King Cole potato chip factory and then at the Jordan Marsh department store (both establishments are long gone), I had a real stereo, real guitars and real amplifiers. Thanks again to Dad, I had my own tape recorder, a big heavy graduation-present Sony TC-540.

The Fashion Jungle poses for a publicity image in Steve Chapman’s basement, 1987. Photo by Minolta self-timer. Hubley Archives.

It was the band work that justified and made real my musical aspirations. From Truck Farm to Airmobile, from the Mirrors all the way to the 1985 incarnation of the Fashion Jungle, all my bands rehearsed in the Hubley basement at some time or other. I extend eternal gratitude to my parents, who were very generous and tolerant of high-decibel band rehearsals two or three evenings a week.

And we had a lot of laughs. I’ll never forget the late-night load-ins after a gig — the gingerly descent with an amp in arms through the concrete bulkhead; wrangling tall, skinny Shure Vocalmaster speakers in through a cellar window; standing in the driveway at 2 a.m. divvying up the buck-three-eighty we made at the door at Geno’s (and keeping my mother awake with our jawing); the jokes and happy exhaustion.

A basement of one’s own

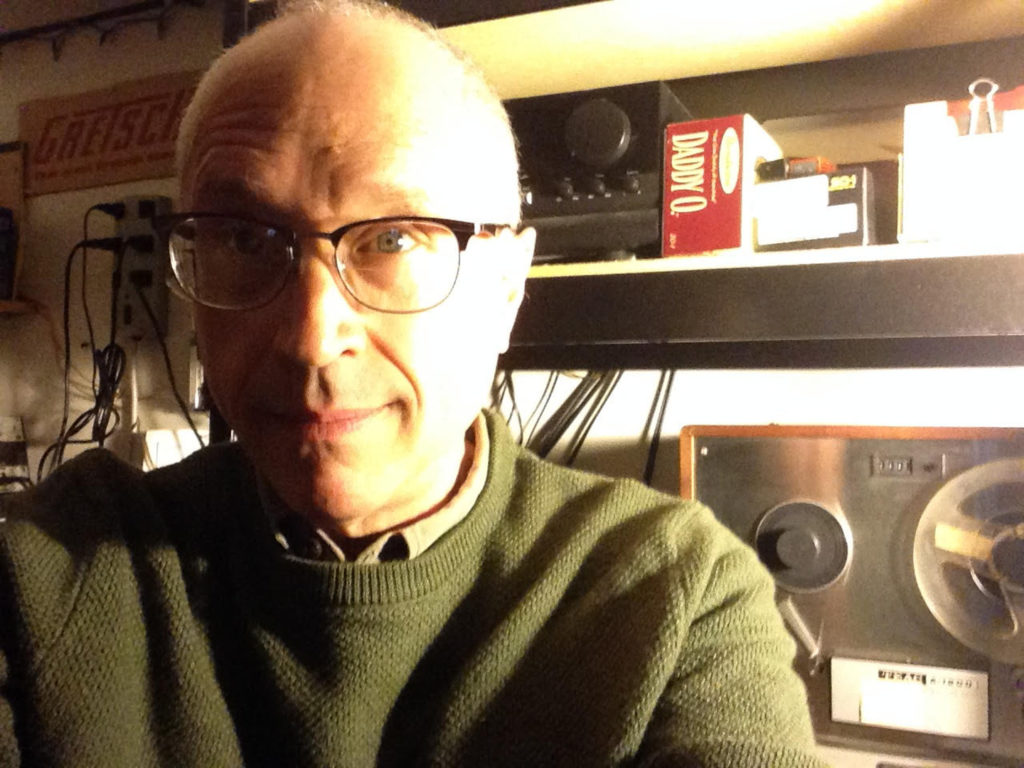

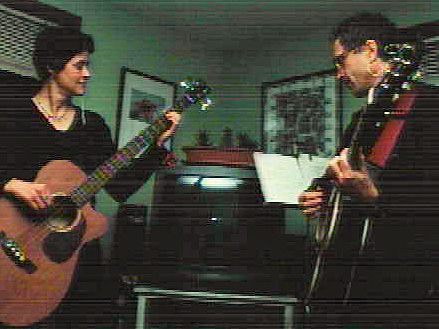

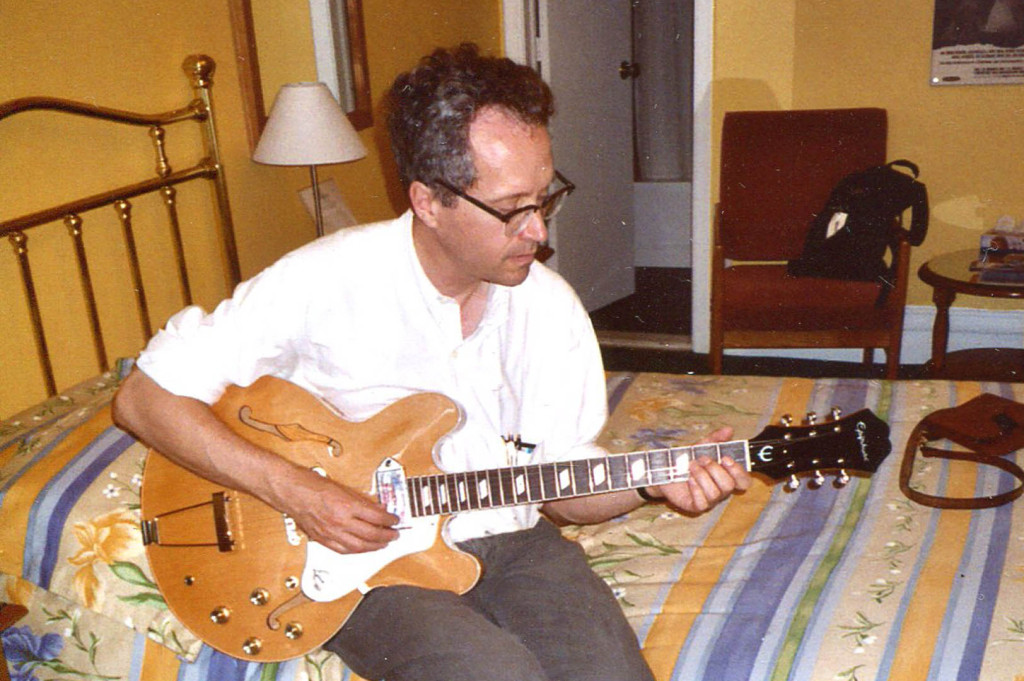

The largest of the four cellar rooms is indeed the music studio. It’s outfitted to a level that would have been incomprehensible to me in 1970, and I work there alone and with Gretchen as the country band Day for Night.

My former studio in parents’ house, after they moved to assisted living and the Dump Guys cleaned it out. Hubley Archives.

But we use our room only when we need the equipment. It’s not a refuge or a hangout, because other parts of the house are much more comfortable. Gretchen and I make much more music in our living room, which is warm and bright and has windows. We even record there, on a digital unit that’s about the size of a sandwich and probably weighs one-fiftieth of the Sony reel-to-reel. (The last times we recorded on tape were in November 2009.)

I didn’t get out much, but I practiced adult activities in that room — being a musician, being in a romance, entertaining friends in sophisticated ways — that I looked forward to enjoying in some sweet empowered by-and-by.

Which happens to be now.

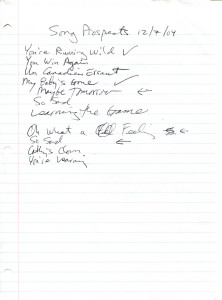

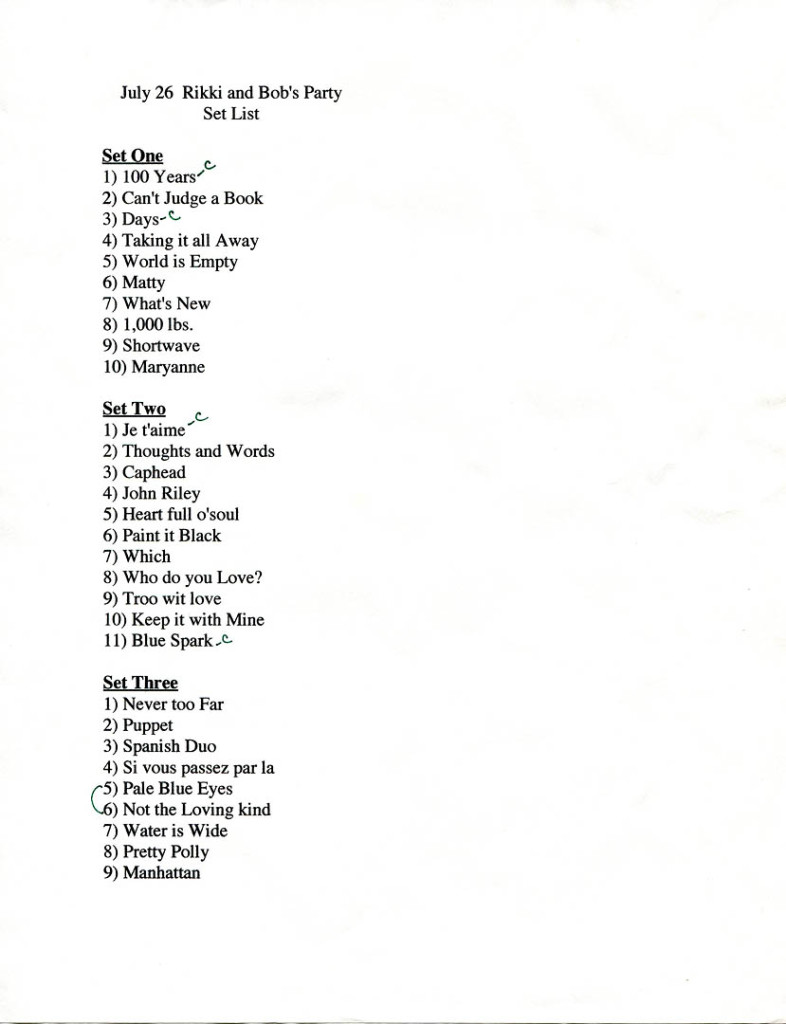

A collection of notes, as in musical, from some different basements. (Help me find the old Chevy hubcap ashtray on E-Bay — why not buy the whole album on BandCamp?)

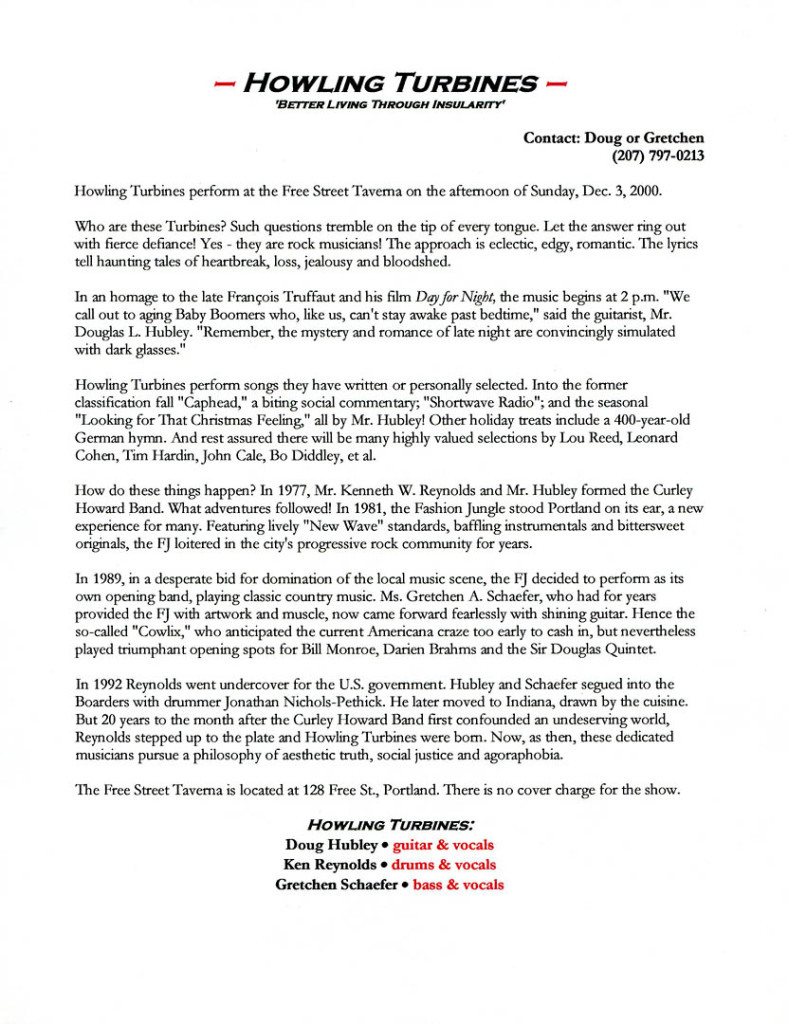

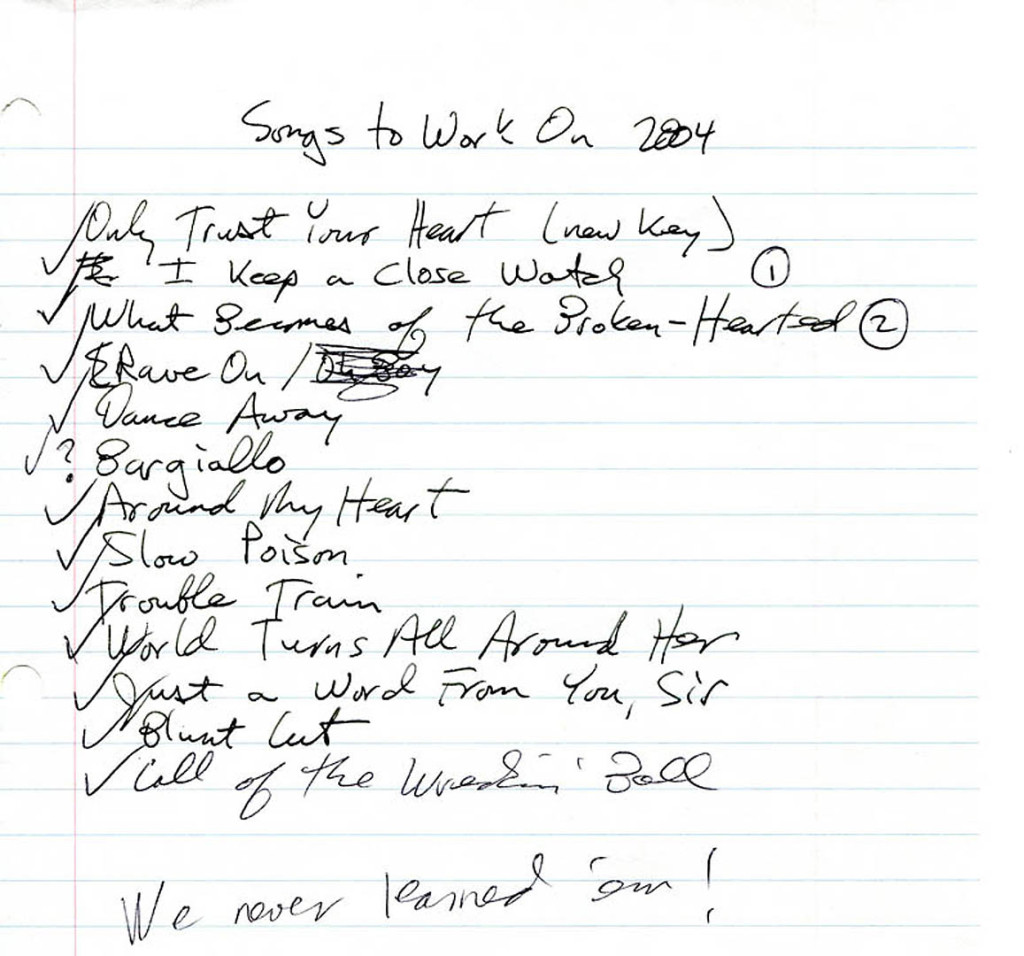

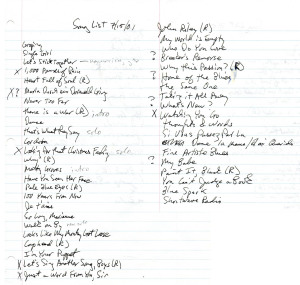

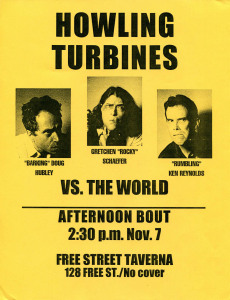

• Caphead (Hubley) The Howling Turbines: Doug Hubley, guitar and vocal • Gretchen Schaefer, bass and supporting vocal • Ken Reynolds, drums. Recorded in the current basement, Aug. 8, 1999. In the late 1990s, I started seeing all these young guys wearing ball caps, driving around in small cars and looking coldly murderous. A fatal fight among some of them in a Denny’s parking lot one year gave me the first verse. (“Caphead,” “Don’t Sell the Condo” and “Let the Singer” copyright © 2010 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved. ASCAP.)

• Candy Says (Reed) The Karl Rossmann Band in Ben and Hattie Hubley’s basement, winter 1981. Our exploration of the Velvet Underground songbook hits a high point as Jim Sullivan’s perfectly ingenuous vocal nails the spirit of this lyric. Jim, lead vocal, guitar • DH, supporting vocal, lead guitar • Chris Hanson, supporting vocal • Mike Piscopo, supporting vocal, bass • KR, drums.

• Don’t Forget to Cry (B. Bryant–F. Bryant) Day for Night recorded this on tape in the current basement, November–December 2006. I piled up guitars, bass and tambourine on the four-track for Gretchen Schaefer and I to sing over. The remarkable thing about my relatively sophisticated recording technology is that in spite of it all, the sound quality of my recordings has hardly advanced over the cheesy stuff I made in the 1970s. To thine own self be true.

• A Certain Hunger (Chapman) The Fashion Jungle at Mr. & Mrs. Hubley’s, September 1983. Steve Chapman, bass, and vocal • DH, guitar • Kathren Torraca, keyboard. We were rehearsing with a drum machine because KR was sidelined with a baseball injury. One of my favorite songs by Steve, and a worthy addition to the my-lover-is-a-vampire school of romantic art. (“A Certain Hunger” copyright © 1983 by Steven Chapman. All rights reserved.)

• When I’m Up I Can’t Get Down (Telfer–Prosser–Jones) The Boarders: DH, guitar and vocal • GS, bass • Jonathan Nichols-Pethick, drums. A fabulous song by a hit-or-miss Celtic rock group, Oysterband. I have neither the dignity to spare nor the constitution for the lifestyle depicted here, but I sure can relate. A staple of the Boarders repertoire, one of my all-time favorites, recorded in the current basement on Oct. 15, 1995.

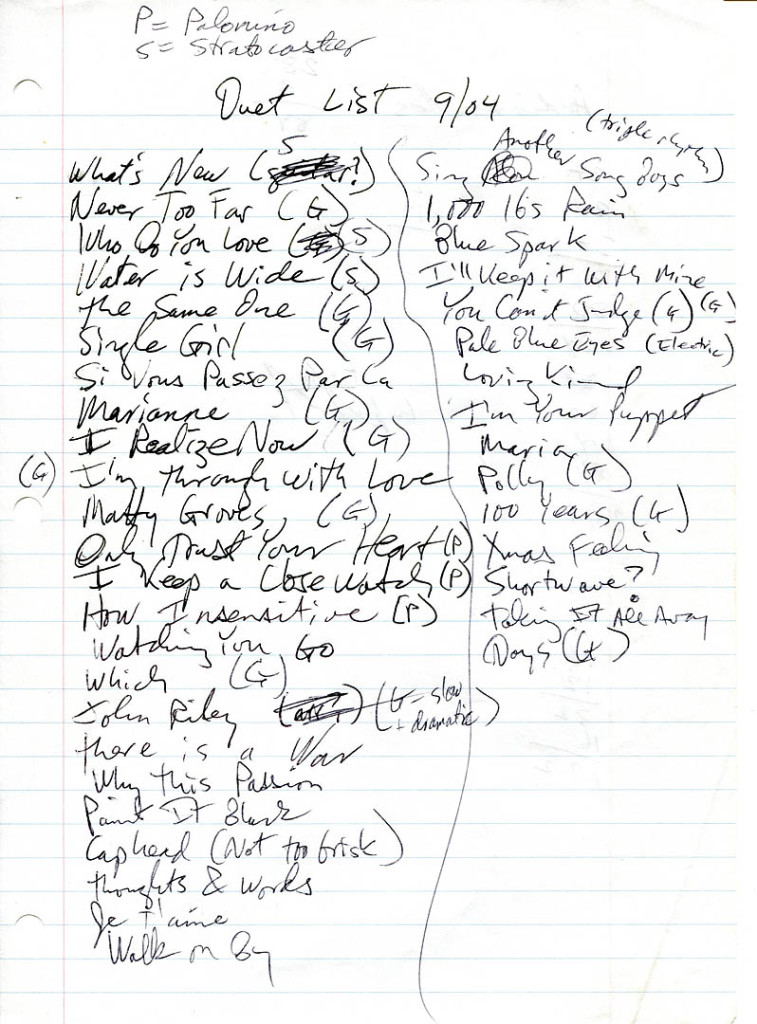

• Polly (Clark) Day for Night: GS and DH, guitar and vocal. D4N had a Gene Clark jag that resulted in our learning four of his songs in one gulp in autumn 2008. Gretchen contributes an especially fine lead vocal on Clark’s mysterious “Polly.” Recorded in the current basement, Nov. 25, 2009.

• Don’t Sell the Condo (Hubley) The Fashion Jungle: SC, DH, KR. One of my favorites of my songs and, I think, one of the Fashion Jungle’s best — too bad few people ever heard it. Gretchen knew an art dealer whose charismatic lover, prominent in the Old Port scene, was rumored to be a coke dealer, woman beater, Satan in the flesh, etc. This is the couple’s story as I imagined it. I wrote the lyric over gimlets in the lobby of the Eastland Hotel on a snowy afternoon while waiting for Gretchen to get out of class. This recording comes from a videotape that she made of the FJ in the Chapmans’ basement early in 1988.

• She Lives Downstairs (Hubley–Piscopo–Reynolds–Sullivan) The Fashion Jungle: DH, lead vocal, lead guitar • Mike Piscopo, backing vocal, rhythm guitar (we were both playing Gretsches, hence the groovy sound) • KR, drums • Jim Sullivan, bass and backing vocal. Directly descended from the Mirrors via the Karl Rossmann Band, the FJ was our gesture at faster-louder-more fun music. We put an emphasis on original songs, but because none of us was a prolific writer, we undertook an ongoing exercise in collaborations like this. The Ken Reynolds lyric was based on an actual person. Recorded in Mr. and Mrs. Hubley’s basement, spring 1981. (“She Lives Downstairs” copyright © 1981 by Douglas L. Hubley, Michael Piscopo, Kenneth Reynolds, Jim Sullivan. All rights reserved.)

• Let the Singer (Hubley) One of my few 1970s compositions that have held up. It’s a paean to the live fast–die young lifestyle that seemed very romantic until all those musicians I liked died young. This is a 1978 solo recording, done in my parents’ basement, for a submission to a WBLM-FM songwriting contest. (How could I not have won?!?)

Notes From a Basement text © 2017 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.