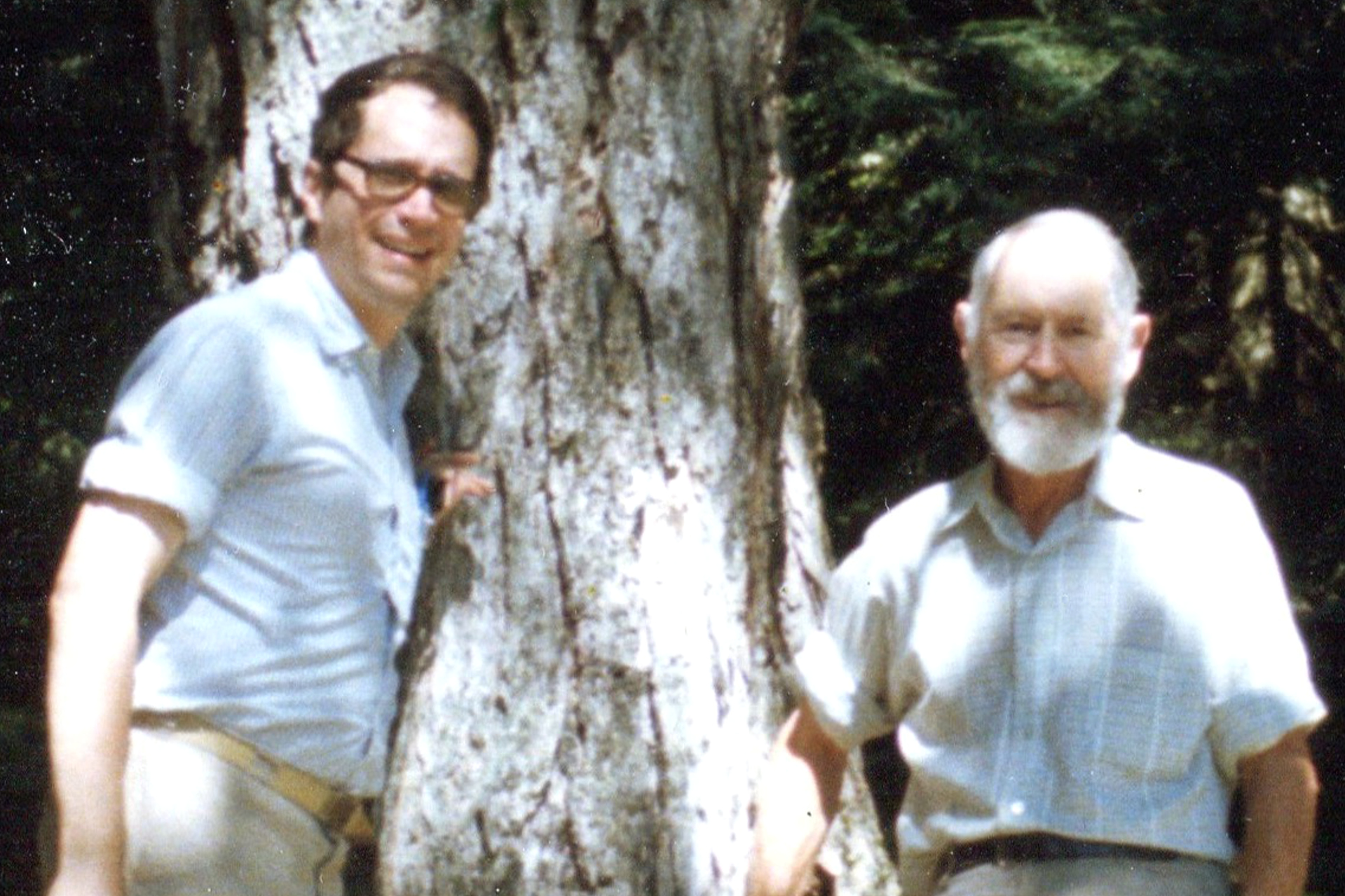

Young Man, Old Man

Doug Hubley, at left, and Ben Hubley pose for the self-timer during a 1987 camping trip to Fayette, Maine. Dad was 66, the age I am now; and I was 33, Dad’s age when I was born. Hubley Archives.

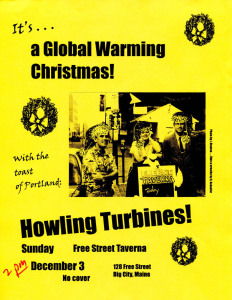

Is it too depressing to plow through tedious musings about aging? Cut to the chase and hear the new EP!

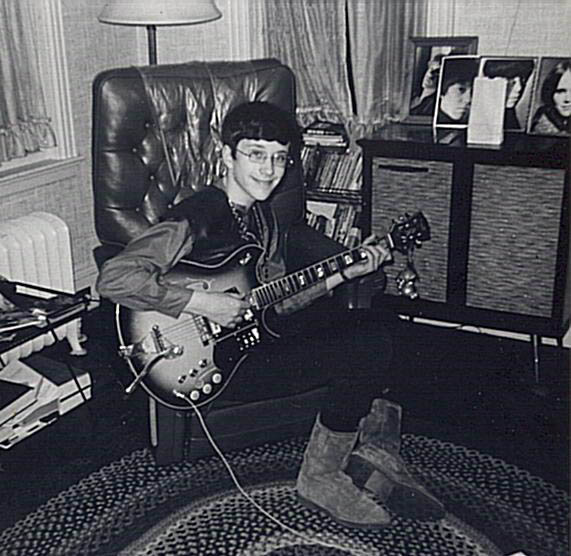

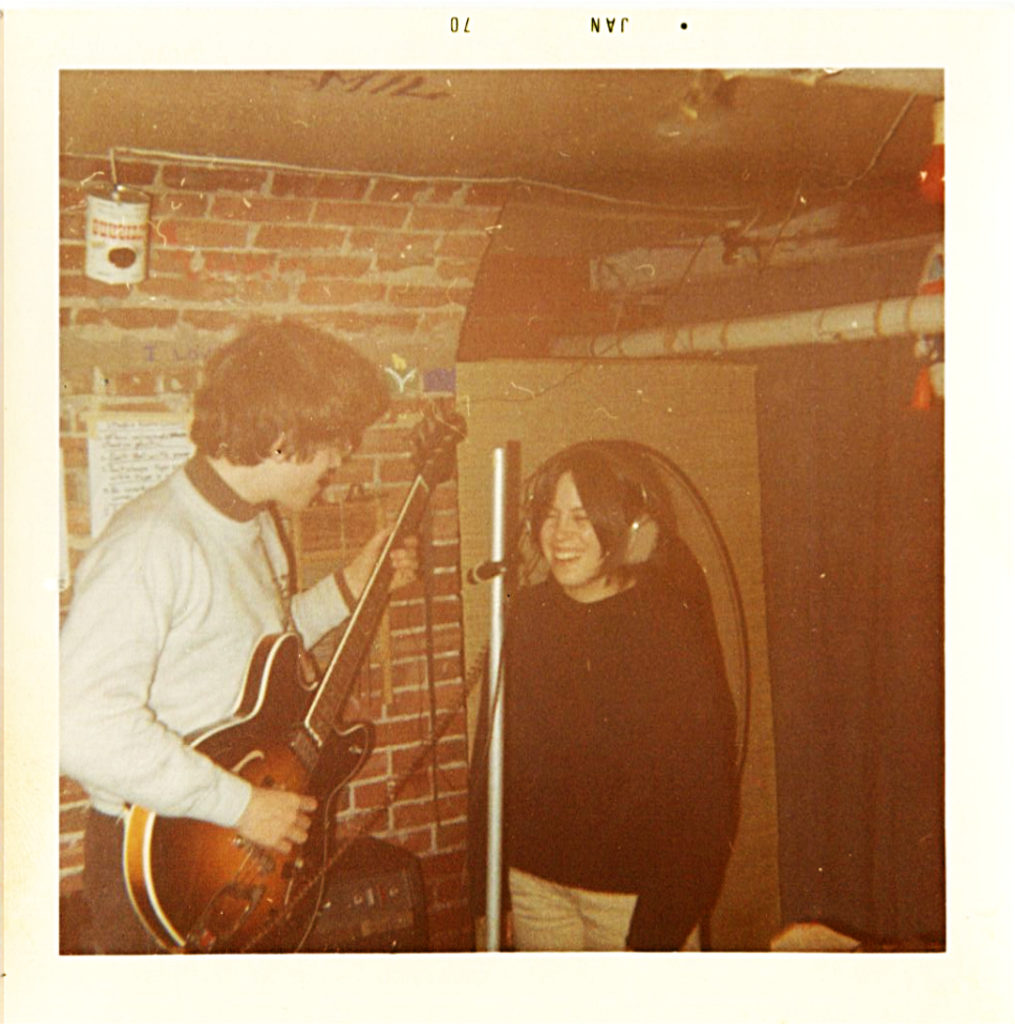

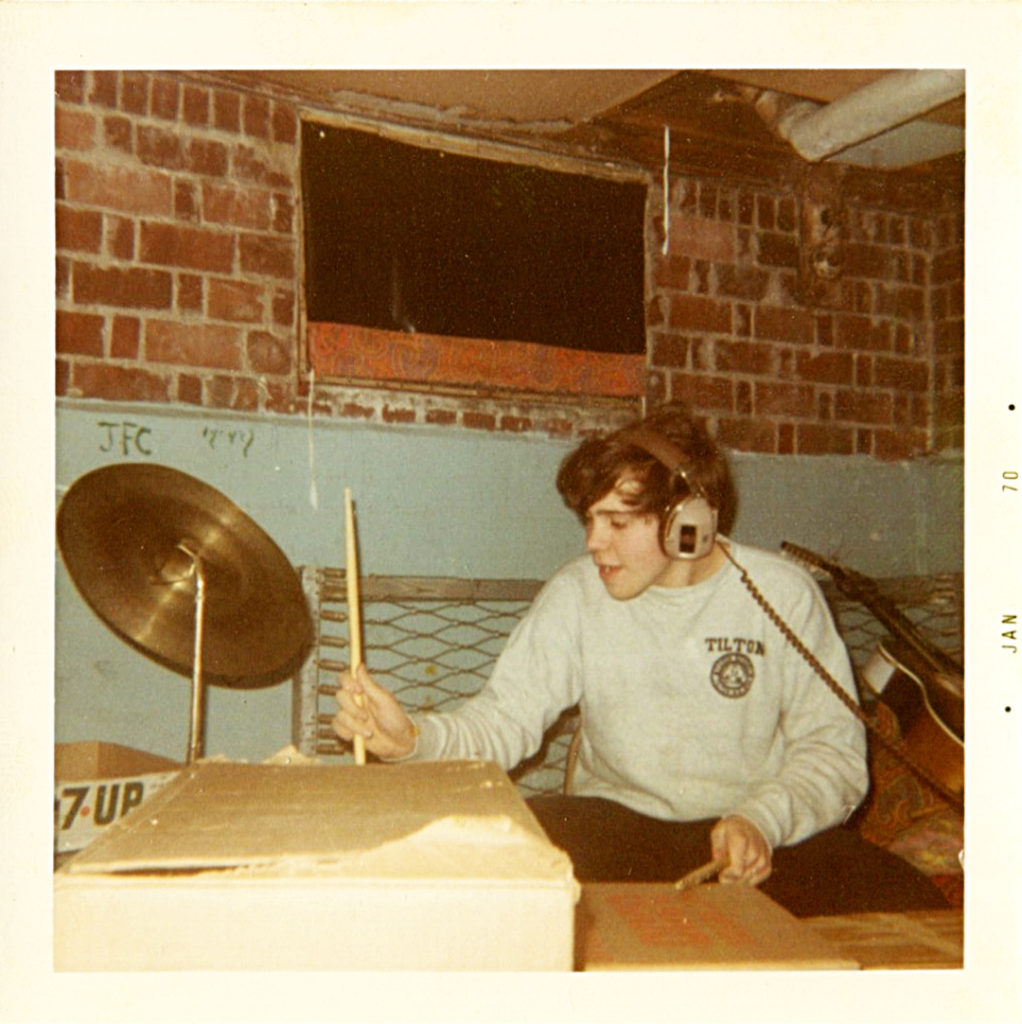

In 1974, when I was a callow 20-year-old,

I recorded French pop singer Charles Aznavour’s “Yesterday, When I Was Young” in my parents’ basement.

I’d heard Aznavour’s 1964 version, “Hier encore,” thanks to my sister Susie, a big Aznavour fan. I loved the melody, and the drama of his recording. And I loved his words — or so I thought.

In reality, I didn’t actually know Aznavour’s words because I don’t speak French. Instead, like many others, I sang Herbert Kretzmer’s English translation, which was widely familiar from Roy Clark’s 1969 hit version. Aznavour and Kretzmer tell the same basic story, that of an older man lamenting his misspent youth. But the specifics are quite different.

And I had no clue that in Aznavour’s original lyrics, the narrator was a man late in life looking back at himself as — wait for it! — a callow 20-year-old.

Aznavour’s lyric, in fact, towers over his longtime translator’s. Where Kretzmer sacrifices poetic force to conform to a rhyme scheme (“weak and shifting sand,” yikes!), Aznavour focuses on detailing, pointedly, the many, many ways a smart young man can be a jerk.

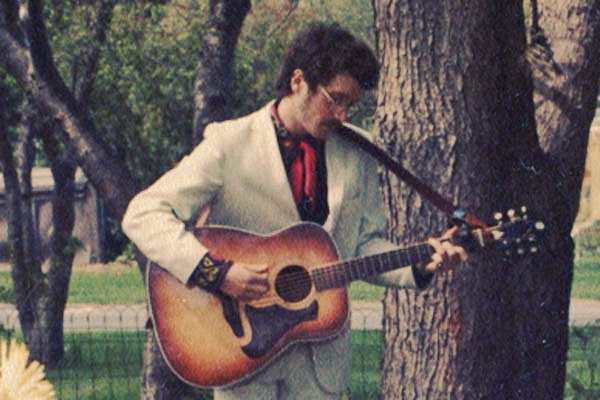

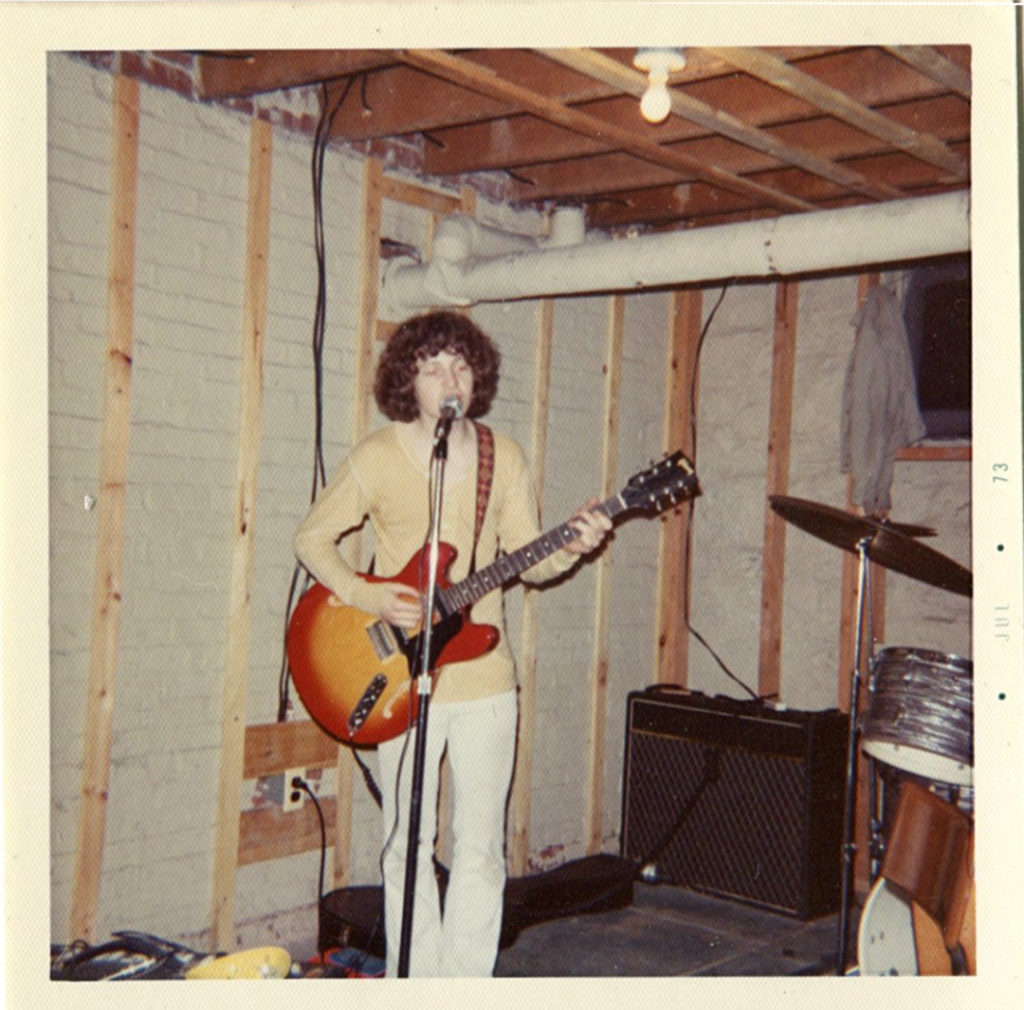

Old man inside a young man: 20-year-old Doug Hubley performs “Wild Horses” on the Silvertone 6-string at Nancy Hubley’s wedding, May 1975. Hubley Family photo.

So maybe it was good that I didn’t know the original lyrics when I recorded it. Maybe Kretzmer’s interpretation was right for me at that point in time. Soggy regrets about things that I’d never experienced seemed to suit my 20-year-old mood better than a hard look in the mirror. (Not that I shied away from mirrors.)

But the bigger issue is: Why, at that promising age, with so much of life ahead of me, did I feel compelled to assume the persona of an old man bitter with remorse over past mistakes?

Callous as well as callow in my 20s, was I displacing into fiction feelings of guilt about my youthful hijinks? Did I wish to inhabit elderly narrators because aging is associated with wisdom, and I’m insecure about my intellect?

Did I think the older, wiser, sorrier image was attractive? Was there a connection with my tendency to seek control of unwanted situations by envisioning how they will end?

Like Jim Reeves, I wonder, I wonder — but I really don’t want to know.

At the time, performing “Yesterday, When I Was Young” struck me as highly romantic, or least as a way to channel my bleak outlook into something decorative. I had no job nor lover nor any clear path toward what I wanted out of all that life, beyond emoting into the Sony reel-to-reel.

Anyhoo, whatever my motivations, learning the song was absolutely a good music lesson. Aznavour’s melody is elegant, a chain of perfect phrases that link and then break away as the long line progresses from wistful to bitter to tragic. It felt good on my brain to figure out the chords and learn to sing over them. It was a welcome challenge to my musical foundations in rock and country.

Older and slightly wiser, I’d achieved some critical distance by 1985, when I made my band learn “It Was a Very Good Year,” Sinatra’s hit of 20 years prior. I still aspired to the regretful roué persona, but now was able to season it with some irony. (As opposed to having the irony present itself 45 years later, as with the Aznavour song during the writing of this post.)

It’s also true that Ervin Drake’s “Very Good Year,” unlike “Yesterday, When I Was Young,” is not about guilty second thoughts. In fact, it’s the opposite — a self-congratulatory review of the Ages of Man, Horndog Division (although the sexy talk is gone by the final verse and with it any charm in the lyrics, as evocative images of perfumed hair and snogging in the back of a limousine give way to, yikes again, the self-satisfied “fine old wine” stuff. Bartender, make mine remorse).

Well, ’nuff said about the lyrics. But Drake’s minor-to-major melody, twining through a chordal structure closely anchored to D, was quite compelling. “Very Good Year” was first recorded by the Kingston Trio, it made the charts with Sinatra, and its composer was American — but Drake’s melody had the same exotic appeal to my uninformed brain as the Eastern Mediterranean music I was enamored of in the 1980s.

So my band the Fashion Jungle learned it, complete with a Richard Thompson guitar treatment that would have been the cat’s pajamas if I could play like Richard Thompson. And the same year we learned it, I forced a tape of our version on poor Richard after his Bowdoin College performance, which I’d previewed for the Maine Sunday Telegram, complete with Thompson interview. I don’t want to know what he thought of the FJ, but I’ll never forget him, sweaty in his pink suit, backing away from me apprehensively as I approached with the tape.

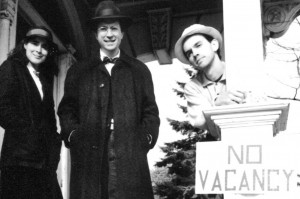

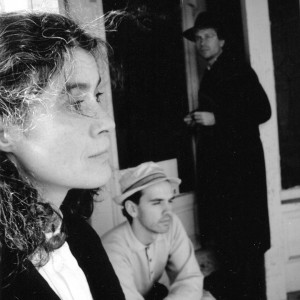

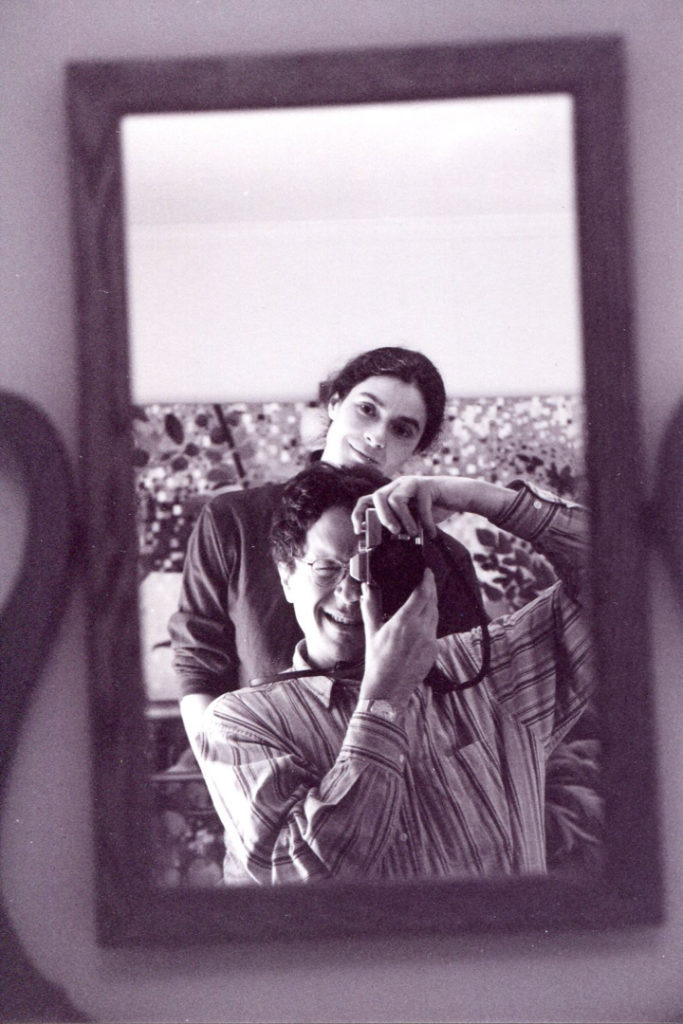

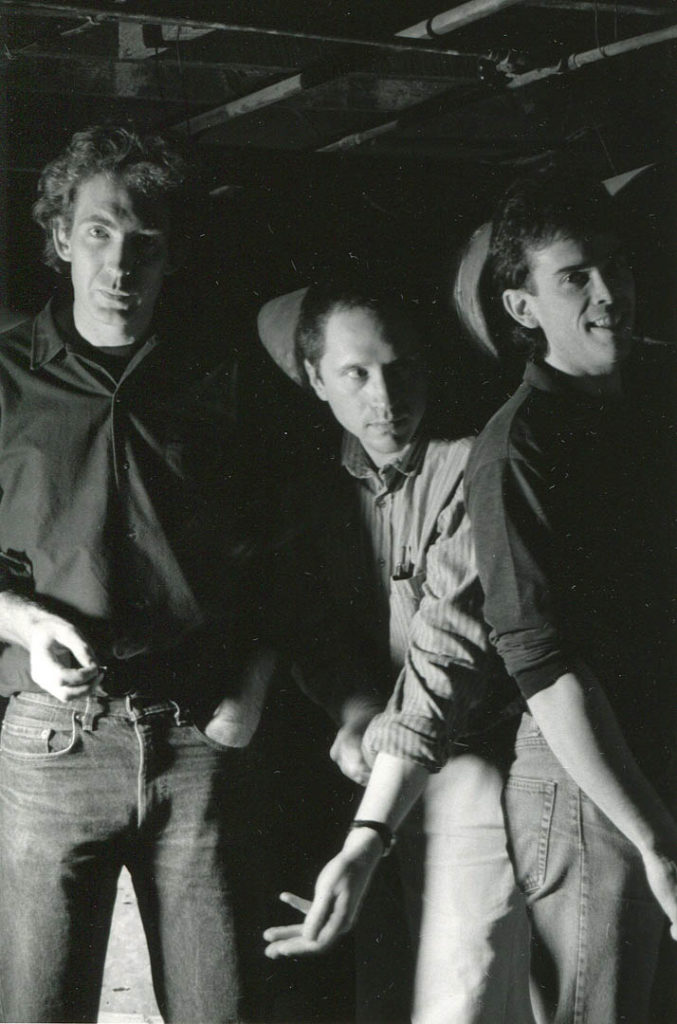

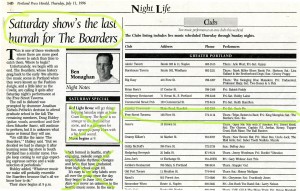

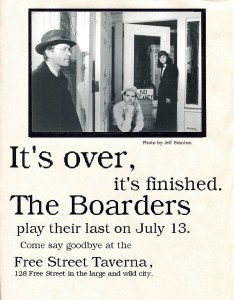

The Boarders striving for a bygone look in a 1994 publicity image by Jeff Stanton. From left: Gretchen Schaefer, Jonathan Nichols-Pethick, Doug Hubley. Hubley Archives.

Today, 26 years later, though I don’t wallow in them anymore, I still enjoy musical elegies for lost youth — “September Song,” “When the World Was Young,” etc. (And we just discovered Hoagy Carmichael’s “Rockin’ Chair,” only 90 years late.)

And then, in an altogether different vein, there’s Waylon Jennings’ version of “A Couple More Years,” the Dr. Hook song whose narrator makes plain to a younger lover the pitfalls of their May-August relationship.

In fact, I think Waylon’s willingness to play the world-weary elder, something he shared with Willie Nelson, is a reason that I like them both. I could never sing Waylon’s “Slow Movin’ Outlaw” with a straight face, but as maudlin as that song is, the crack in Waylon’s voice and the loss in Dee Moeller’s lyrics — and, of course, the railroad frame of reference — get me every time:

“All the old stations are being torn down

And the high-flying trains no longer roll

The floors are all sagging with boards that are suffering

From not being used anymore

Things are all changing, the world’s rearranging

A time that will soon be no more

Where has a slow-movin’, once quick-draw outlaw got to go?”

But as much as I liked them, I never performed many of those songs nor did I regret not doing so. I guess it’s a healthy sign that as I finally learned to enjoy my fast-passing youth, I became less interested in fictionalizing it.

And a sharper corrective came from the punk-rock scene in Portland, Maine. Punk’s be-here-now ethos, its acid anti-sentimentality — especially when the sentiment was nostalgia — made a deep impression on me. (Still, I bet there’s no shortage of people my age nostalgic for their punk years.)

So I learned to think twice before waxing nostalgic in unfamiliar company. (Good training for one’s 60s, especially during 2020, a year that has lowered the bar for what might qualify as the Good Ole Days.)

More important, I started to understand the emotional uses, good and bad, of nostalgia — how it can comfort, how it can anesthetize, how it can co-opt, how it can deflect, how it can be weaponized. (Could there be such a thing as an ethics of nostalgia? Yep. Try it on Google.)

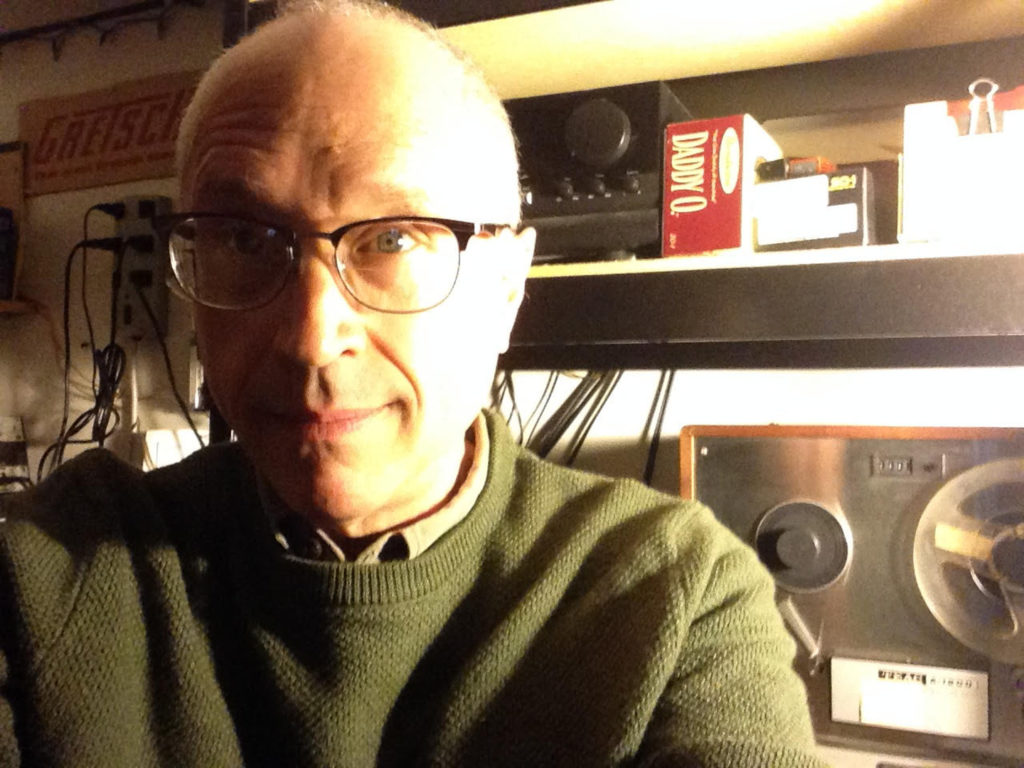

In any case, in 2010 they moved me to a new cubicle in the Tower of Song (actually the Tower of Song annex out by the Maine Mall), and a couple years later I made my own contribution to the catalog of songs that view youth across the wide river of age. They say you shouldn’t drink alone, and my song “I Never Drink Alone” is about someone who is saved from that habit only by the ghosts and memories keeping him company at the bar.

I’m blessed to still have loved ones in my life (if not so many as in 2012), but then, well into my 50s, I was looking ahead. (See “control of unwanted situations,” above.) “I Never Drink Alone” is one of the truest songs emotionally I have ever written, a picture of mourning what’s lost and fearing how one mourns.

Three years later, “Just a Moment in the Night” came along. Like “I Never Drink Alone,” it comes straight from the heart. But typical me: I finally manage to write a love song after 50 years, and instead of a celebration, it’s another frigging elegy for times past.

In other words, I’ve arrived: I have become that retrospective old man I thought I wanted to be all those years ago, when I was strumming the Silvertone and turning the Shure Vocalmaster reverb to 11. Then a young man assuming the role of an old man, I’m now an old man looking back at the youngster and thinking: twerp.

Yes, I’m an old man; and regrets, I have a few, as Paul Anka whispered in Sinatra’s ear. (Sinatra, according to Wikipedia, didn’t actually like “My Way,” although I imagine he gritted his teeth and deposited the royalty checks anyway. I don’t like it either, although Sid Vicious’s version is funny — the first time.)

Would I have written “I Never Drink Alone” and “Just a Moment in the Night” in the 2010s if I hadn’t loved “Yesterday, When I Was Young” and “Slow Movin’ Outlaw” in the 1970s? Would such odes to longing and regret, sung in the December of one’s years, yada yada, still resonate so strongly if I heard them for the first time only now, in my 60s?

Beats me. Doesn’t matter. Relatively few things really do, as one discovers in one’s golden years. Old age comes with its own very special concerns, and they seem far removed from the rampaging lusts and hot tears of youthful folly. Regrets, I have a few, and they’re pretty much about arthritic feet, dwindling energy and loved ones we’ve lost.

So at last I understand the listeners who most closely identified with those songs, as opposed to the callow 20-year-old looking for a persona. I’m not quite the narrator in those songs — too lucky, even happy, for that — but we nod “hello” when our paths cross at the bar. Really, I’d rather drink the fine old wine from vintage kegs than waste it on a metaphor.

We mourn the past that’s gone, we regret the hurt we caused. But we don’t regret the powers, and the opportunities to use them, that we had. Little did I know, when I was wandering through the Seine River fog of “Yesterday, When I Was Young” all those years ago, that the regrets for one’s lost youth would seem more and more like a luxury?

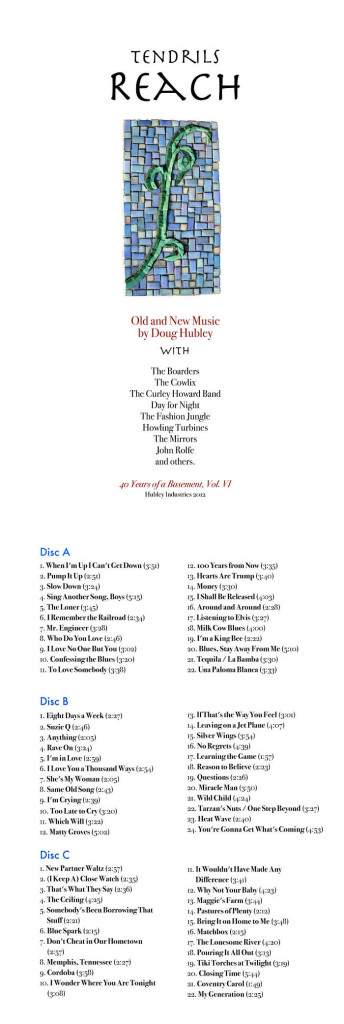

These three songs

resulted from a summer 2020 push to record music for this Notes post*. Here are three diverse takes on getting older. On the first two, it’s all me in front of the mic. “Beyond the Great Divide” is a Day for Night recording featuring Gretchen Schaefer on harmony vocal. (See the EP on Bandcamp.)

- I’m an Old, Old Man (Tryin’ to Live While I Can) (L. Frizzell)

- A Couple More Years (S. Silverstein–D. Locorriere)

- Beyond the Great Divide (J. Crowley–J. Routh)

*as well as for a new website showcasing my original songs.

Notes From a Basement copyright © 2012–2020 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.

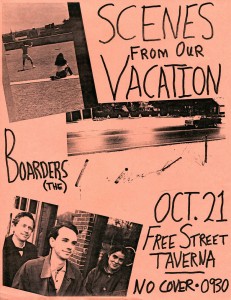

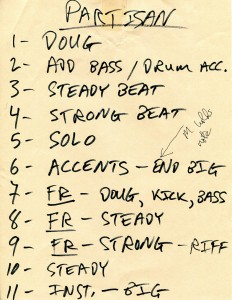

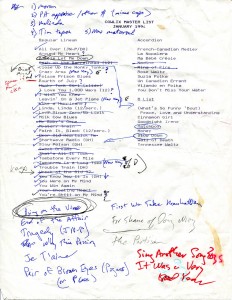

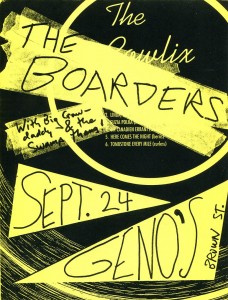

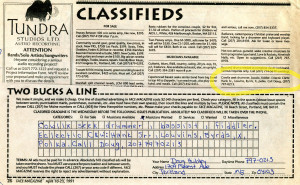

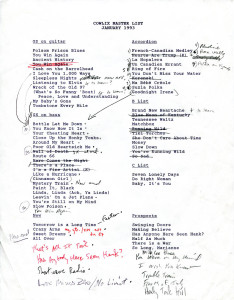

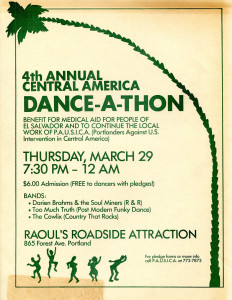

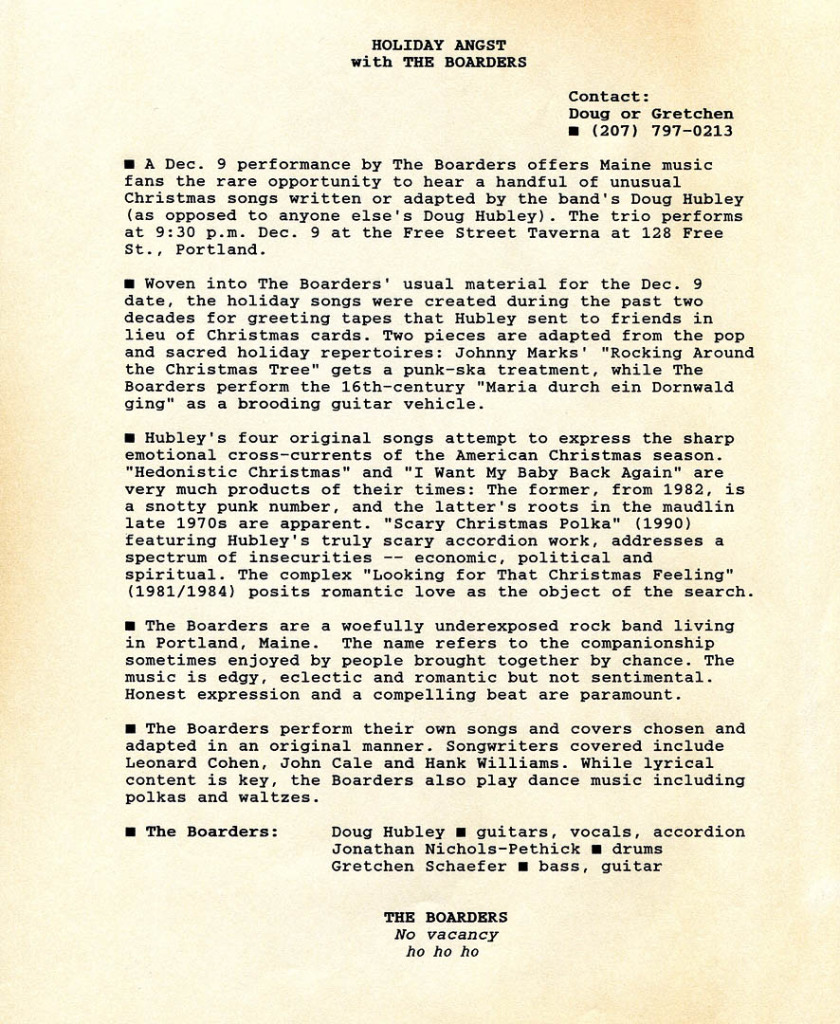

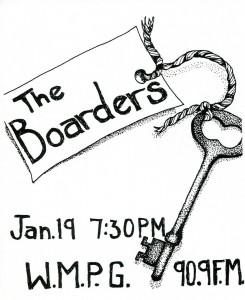

![Late in the 1860s novel Little Women, heroine Jo March, dreading her friend Laurie’s budding romantic feelings for her, tells her mother she feels “restless and anxious to be seeing, doing and learning more than I am.” Her solution is to move to the city, to live and work in a boardinghouse. There, she has a room to herself, time to write, and the welcome distraction of friendships with her fellow boarders. — Ruth Graham, The Boston Sunday Globe, Jan. 12, 2013 [Week of March 24] Boarders Let's begin with something deceptively obvious. Larger musical groups are empowered by their capacity for complexity. Smaller bands are empowered by the need to keep it simple. Obvious, for sure, but for the musicians involved, it's a powerful reality that encompasses infinite subtleties in both directions -- perhaps unexpectedly so in the case of the minimal. The richness of potential there can be highly gratifying. Every time I have gone from a larger to a smaller band, I've felt suddenly light, ready to fly. This was especially true in the case of the Boarders, the trio remaining after two musicians departed our so-called country band, the Cowlix. Singer Marcia Goldenberg left in March 1994 and violinist Melinda McCardell in May, after one last gig. My fellow remnants were Gretchen Schaefer, who played bass and guitar, and drummer Jonathan Nichols-Pethick. I played guitar and accordion, proposed much of the material and sang most of it. Post-Cowlix, we wasted little time finding a direction. And circularly enough, our direction was to be the Boarders. Atop a hard core of held-over Cowlix country and folk-dance repertoire, we added pop-rock by Buddy Holly, Jackson Browne and others. I was gratified to bring in two songs by Tim Hardin, one of my first big influences, to the repertoire. We learned two by the Kinks; the Oysterband's brilliant "When I'm Up"; Anne Savoy's adaptation of the Cajun song "Mon Chere Bebe Creole." From the torch song catalog came "What's New" and "I'll Be Seeing You." We glommed up enough Leonard Cohen to jokingly bill ourselves as Portland's only L.C. tribute band, even tackling the French Resistance anthem "The Partisan," which Lennie covered on his second album. And we revived several originals by my pre-Cowlix combo, the loudly romantic Fashion Jungle. Speaking of which, among other improvements that came with the Boarders, it was here that I felt at home as a songwriter again after five years adrift. It was ironic, or at least telling, that toward the end of the 'Lix I was thinking about revisiting Fashion Jungle material (and we even picked up "Shortwave Radio"). Apparently I am on a short chain fastened to a post in the ground, because I walk in one direction until the chain is wrapped completely around and then I wind it again the other way. In the four years of the Cowlix, I wrote two songs: "Slow Poison" and "Trouble Train." In the two years of the Boarders, I wrote three, including two that I consider among my best, "1,000 Pounds of Rain" and "Watching You Go." And for the first time since the Fashion Jungle, I wasn't the only songwriter in the band. We hung onto Jonathan's "All Over," and he and his wife, Nancy Nichols-Pethick later presented "Tragedy." Nostalgia wears rose-colored contact lenses, but it seems to me that our musical interests were as harmonious as everything else about the Boarders. I don't recall Gretchen, Jonathan and me ever discussing our repertoire in broad or aspirational terms, and neither did we disagree about material. We just brought songs in and, for the most part, played them. It was a relief to lose the country music fiction espoused by the Cowlix, a band with a long stylistic reach and a grasp that almost matched. As previously noted, I, at least, had started violating the "country" descriptor early on. And now here were the Boarders with no such mandate to obey or defy. Like the Cowlix, we had the range to pull off a variety of music, but there was a crucial difference: What the 'Lix lacked and the Boarders possessed was a collective personality focused enough to forge an identifiable sound from some disparate types of music. Much of that personality was purely musical and organic, but -- and I know it will shock and surprise you that such things happen in the music biz -- some slight contrivance went into the Boarders' public identity. The three of us had zero interest in retaining the Cowlix name. Not only did we wish to leave the past in the past (as I am obviously so dedicated to doing), but we had discovered along the way that we weren't the only ones using that name. Pretty obvious moniker for a country band, after all. I don't recall where or how "Boarders" turned up, but it seemed sufficiently random-yet-meaningful, that irresistible combination, to work for this "new" band that seemed capable of anything. The richness of the Boarders' prospects and potential, coupled with my decade-plus experience, as a music journalist, with musicians angling for my attention, prompted a fairly focused publicity campaign. We even created press kits, including a band history (remarkably free of factual content), demo tapes, a sample lyric ("Trouble Train"), publicity photos by longtime friend Jeff Stanton -- and a key pin. Key pin? Just like it sounded: an old-fashioned lever-lock key with a pin-back epoxied onto it, so it could be worn as a pin. The key concept was derived from the boardinghouse concept, and the whole works was derived from my realization that journalists and club owners would be more likely to remember a band that gave them presents. Who doesn't like presents? I have no idea whether the key pins made any difference to our getting work -- although we did get work. But, revisiting the two key pins that I still have from that exciting Boarders efflorescence 20 years ago, I would like to think there are still a few Boarders key pins turning up, from time to time, on the sport jacket lapels and cloche hats of Portland's hip-and-cool.](https://www.dhubley.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Boarders-JS-LEDE-1024x680.jpg)