In Dreams

Make your dreams come true and visit the EP In Dreams at the Bandcamp store!

There is more music in my dreams

than there are dreams in my music.

This despite the fact that in the obsolete rock and country that I play, dream songs abound. And they tend to be of a type: If dream songs touch all sorts of themes and schemes, as Bob Dylan might say, they’re often about broken or unrequited love. (The same is true for the song-lyric theme of losing sleep. Where are the ballads about the kind of broken heart that causes nine hours of unbroken, restorative slumber?)

I’ve never written a song about dreams and aching hearts, but have performed some of the classics. That famous country duo Day for Night — Gretchen Schaefer and I — learned the Louvin Brothers’ “When I Stop Dreaming” 10 or 11 years ago and it’s still on the active list.

So is Lonesome Don Gibson’s “Sweet Dreams of You,” which we added around 2011.

Those examples and many others demonstrate that monetizing poetic or metaphorical notions of dreaming can be a pretty feathery way to feather your nest. The poetry angle is key, though: Real dreams tend to lack commercial potential.

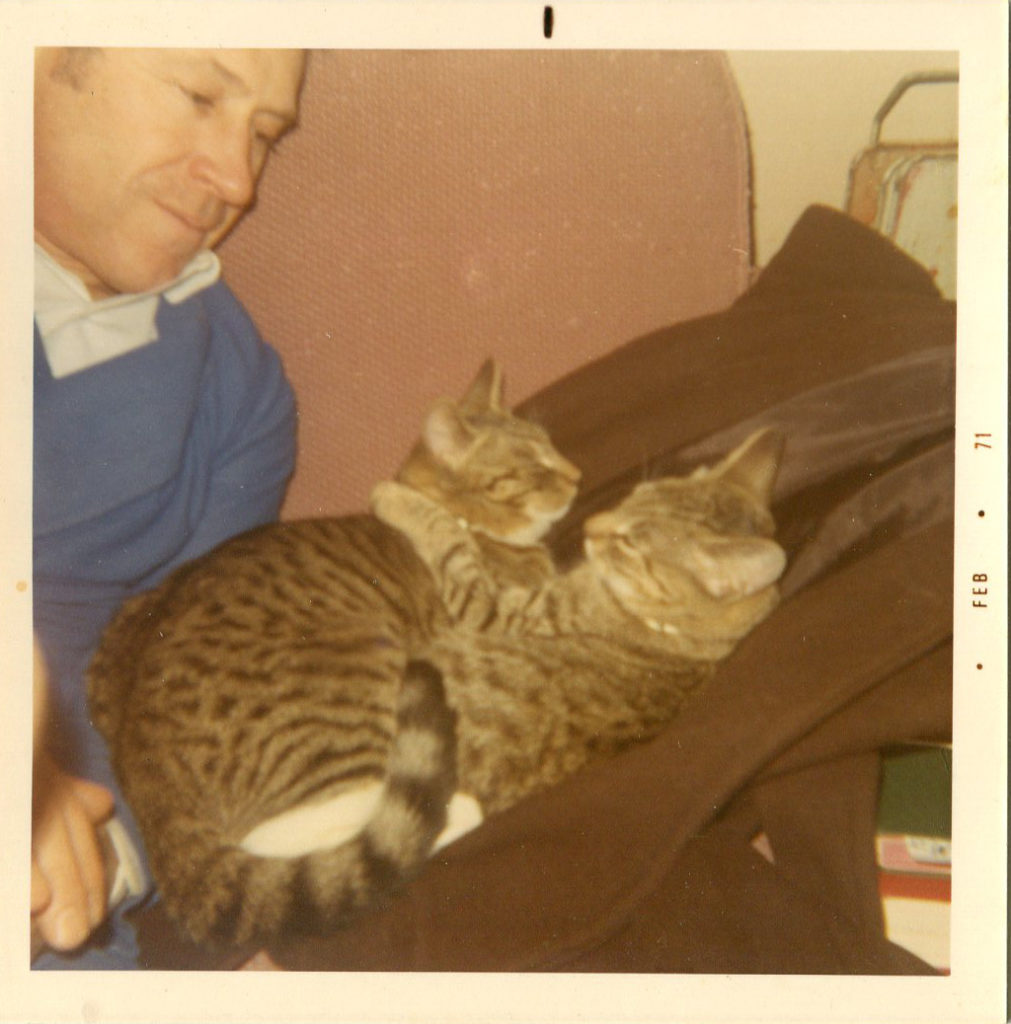

Nowadays my dreams often feature my parents. Ben died in 2018 and Harriette in 2017 — but in dreams they live on, somehow furloughed from the memory-care facility and back at home with their cats on South Richland Street. (In one recent episode, Dad spent $400 on a fraudulent jewelry sale — which in real life he never would have done — and I had to pay it back.)

But I have a few recurring dreams to which music is central.

A particular favorite, not, is the frustration dream in which I am part of an electric band that is setting up for a gig. Showtime approaches and, for whatever stupid dreamlike reasons, we just can’t seem to get things ready. You have your own special versions of this.

Less frequent but more gratifying are the variants in which the setup is accomplished and music is played, often in front of a big wall of amps (which in fact is something I have never experienced. A Super Reverb is the largest amp I’ve ever owned).

Often the dream ends as the music begins. I’m a writer and a musician, but in my dreams I don’t really hear music and I can’t read anything.

Then there’s the bad dream in which I am supposed to perform — on accordion — with the Portland String Quartet or someone similar. But I am realizing, just before the concert, that I haven’t rehearsed with them and I don’t in fact read music. (My accordion, simultaneously, dreams that it’s going on stage in its underwear.) That dream derives from the years I spent previewing and reviewing classical concerts in Southern Maine.

In my mid-teens,

I had a non-musical recurring dream about a small cabinet in my room. (Now painted in black enamel, the cabinet remains in use as our TV stand.) The dream was simple: The cabinet was stuffed full of new pullover shirts, made of velour and very groovy in a mid-1960s quasi–Star Trek style.

In the dream, so many of these alluring shirts were jammed into the cabinet that the door wouldn’t shut and the shirts came tumbling out.

In the dream that we call real life, I actually owned shirts like that — but only two. One was a rancid olive green and had a leather string and eyelets to cinch up the collar. Loved it! The other was a turtleneck in blue and black stripes. Wanted to love it! But even I recognized (finally) how ridiculous I looked in it.

That dream stays with me because it vividly represents a dreamy perception of a cornucopia of desirable things lingering just outside reality, so close that it could be just outside the room that I’m in, on the back step like the latest Amazon delivery; so close that it’s hard to believe it’s not real.

That sense of a surreal cornucopia existing just beyond existence crops up again in the recurring musical dream that affects me the most: a dream about a reel-to-reel tape of simply great music that I have written and recorded. It’s generally electric stuff, it’s complex and sophisticated, there are instruments in the mix that I can’t play in real life, and the audio is saturated, immediate, immaculate. It’s the summation of my musical desires and capabilities. It’s my Mylar Holy Grail. (And again, since I can’t really hear music in my dreams, this is all something I just know without benefit of evidence.)

The plot surrounding this masterpiece varies from instance to instance. But generally the tape has been lost and now is found, and it will make all my real-life dreams come true. It’s the conclusive validation of my existence.

In the dream I thread the tape through the machine, the motors hum and the reels turn, the needles jump, the tape follows its course with utter verisimilitude, and the music, I tell you, sounds great. And though it doesn’t much resemble any music I’ve ever made, it’s mine, all mine.

As with my silly velour shirts, the dream is a mist rising from a pool of reality. Broadly speaking, I have watched a lot of tape roll through tape recorders. Specifically, decades ago, intoxicated by naive ignorance and self-importance, I would periodically assemble a “project tape,” a reel that in my mind, if nowhere else, was the equivalent of an album release.

The fact that not more than four or five other people would ever hear these magna opera never occurred to me and might not have mattered if it had. (I think I knew, on some level, that I was just practicing.) There are a few OK songs on those tapes — generally written by my partner in project-taping, Tom Hansen — but all told they comprise a big bunch of bad music bordering on racket, and are hard to listen to today.

I mean, hard for me. I shudder to think what they’d do to anyone else. Musicians: The first commandment is to do no harm!

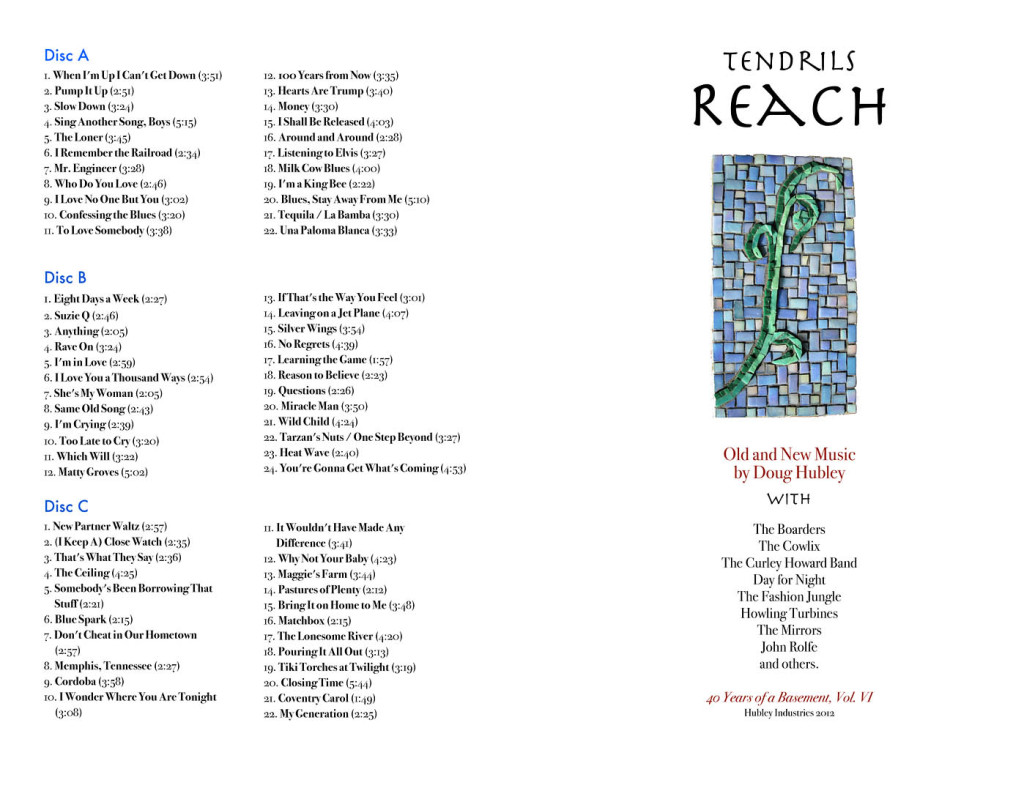

Several people heard, hopefully without injury, the grownup “project tapes” that I made from 2005 to 2011: not tapes, in fact, but a series of CD compilations of music that I’d had a hand in making during the previous decades.

Around Christmastime during those years, I gave the sets to the other performers on the original recordings, because one reason for producing the series was to thank people I’ve made music with for the past half-century.

But another reason, I imagine, was simply that my project-tape impulse is irrepressible.

Of course, it’s all rooted in the same resource: the homemade recordings that have been piling up in one basement or another (or under the bed in banana boxes, etc.) since 1966. Though each 40 Years of a Basement set includes songs recorded specifically for the series, the project was primarily the outcome of foraging through old recordings.

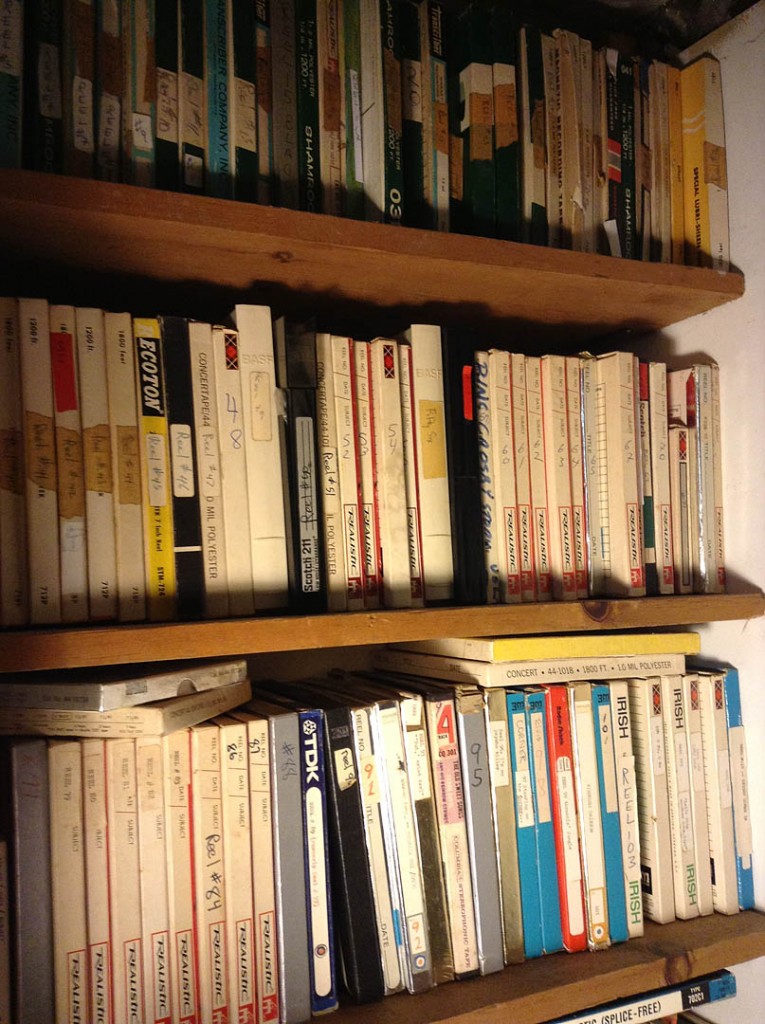

The Tape Catalogue was my guide through that process. I’ve told you about the Tape Catalogue before: two stuffed loose-leaf binders, including one dilapidated veteran from middle school (its cover, like that velour shirt, a rancid olive drab), that list the contents of all those tapes and digital media.

Descriptions for each recording include the performers, recording location and, in most cases, the exact or approximate date of recording. There’s also a lot of blah-blah about the quality of the sound and performances; notes about other circumstances, musical and otherwise, that prevailed during the recording; and, especially in the 110 or so reel-to-reel tapes, most of them from the 1960s and ’70s, a lot of self-scrutiny that was droll at best and naively self-pitying at worst.

Maintaining the catalogue has been a high obligation for me, but no obligation is so lofty that I can’t find a way to fall short of it. (If you see what I mean.) I’m more dutiful nowadays, but there were times when the uncatalogued tapes piled up.

40 Years of a Basement was good in that it inspired me to clear up the catalogue backlog. And it was also good in that it was an analog to that reel-of-tape-as-Holy Grail dream: I found material, new-song demos in particular, that I had lost track of. Some of it was actually pretty good, if not the conclusive validation of my existence.

Eight years have passed since I started on the seventh 40 Years of a Basement set. I add a few items to the collection each year (generally live Day for Night sets), but I visit the tapes only rarely, mostly when I’m seeking something for one of these posts.

I stay away but time is always there, a gently but insistently rising tide that will make all things unknowable, untouchable. For all the life and living they represent, the recordings don’t care. They sit in the basement, waiting patiently and deteriorating slowly, and the Tape Catalogue stands on its shelf ready to serve.

I didn’t start the catalogue as a weapon against time. In 1971, I was 17 years old and time’s tectonic force was the furthest thing from my mind. I was just trying to keep the tapes organized.

Now I do see the catalogue, and all the other documents, as a defense against time’s insistence on nothingness. It’s a Mylar-thin bulwark but it’s what I’ve got. I’ll never lay hands on the cornucopia in dreams, so I’ll continue to cling to the shabby reality within the four walls of the basement.

Dreams are the theme of both the post and the following selection of tunes from the basement.

When I Stop Dreaming (Ira Louvin–Charlie Louvin) Day for Night performing at Quill Books & Beverage, Aug. 5, 2018.

Sweet Dreams of You (Don Gibson) Day for Night performing at Quill Books & Beverage, June 17, 2018.

How Can We Hang On To A Dream (Tim Hardin) A selection from 1995 or ’96 that speaks to the theme of the post not solely in its title, but because I’d lost sight of it until I compiled the first 40 Years of a Basement set. The Boarders: Doug, vocal and accordion; Gretchen, bass; Jonathan Nichols-Pethick, drums.

It’s a Dream (Neil Young) One of the first songs we learned as Day for Night, during the period before we focused hard on country music. We very much enjoyed the Neil Young concert film Heart of Gold. A few days after we saw it, I came home from work and Gretchen casually started playing and singing this song from the film, which she learned on the sly. Gretchen, autoharp and vocal. Doug, accordion.

Notes From a Basement copyright © 2012–2019 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.