Fashion Jungle: End of the Affair

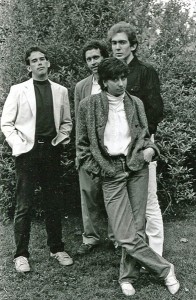

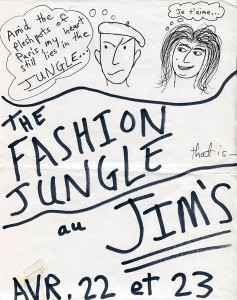

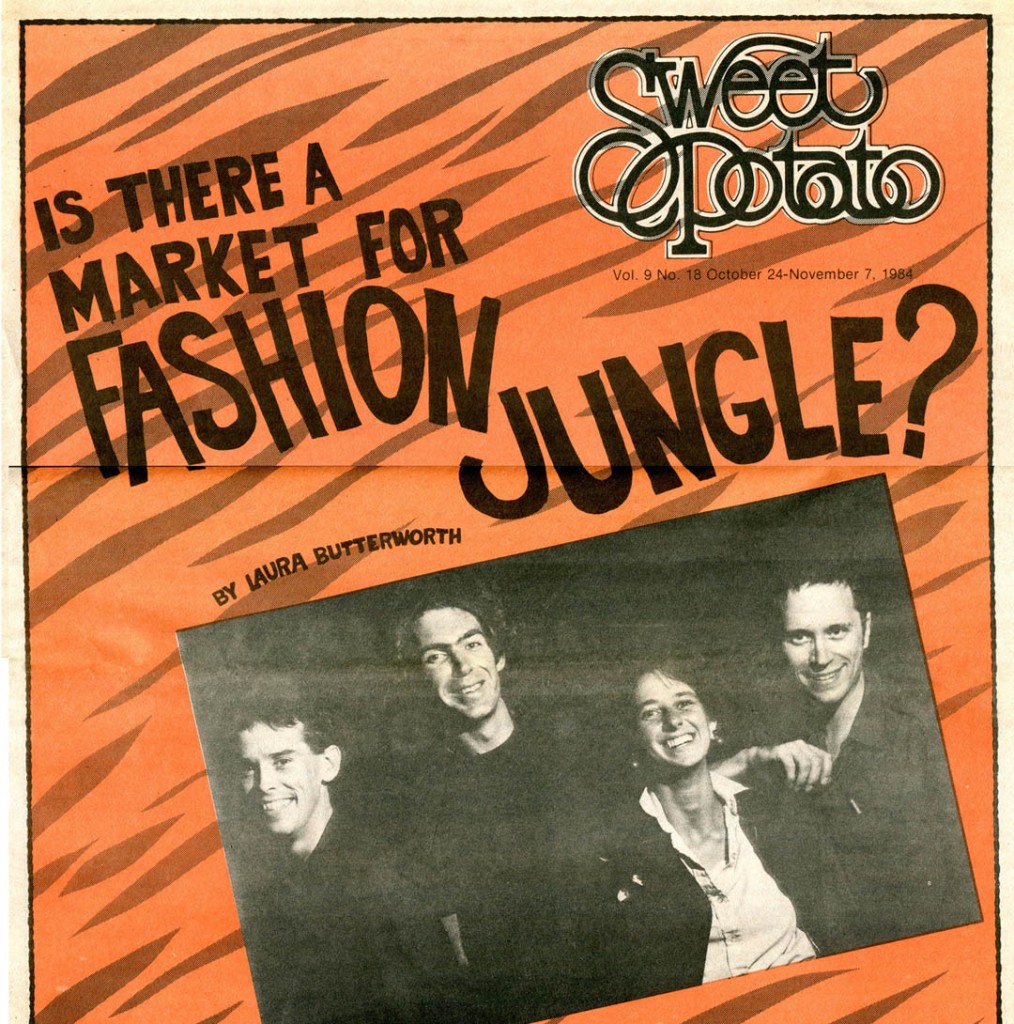

The Fashion Jungle on the cover of the Rolling Stone — er, Sweet Potato. Click to enlarge. Photo: Rhonda Farnham Photography.

No text! Go straight to music!

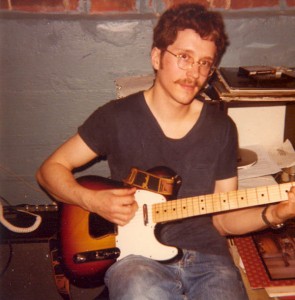

“Any [A&R man] worth his salt would find in Fashion Jungle all the elements of a superstar-group-to-be: Kathren, the fashion plate gal on keys; Doug, the frenetic guitarist who looks like he’s escaped from a biology lab; Steve, the tall, introverted bassist; and Ken, the band’s anchor behind the drumkit.”

― Laura Butterworth, “Is There a Market for Fashion Jungle?”, Sweet Potato Magazine, Oct. 24–Nov. 7, 1984

“It’s deja vu all over again.”

― Yogi Berra, master of quotable quotes

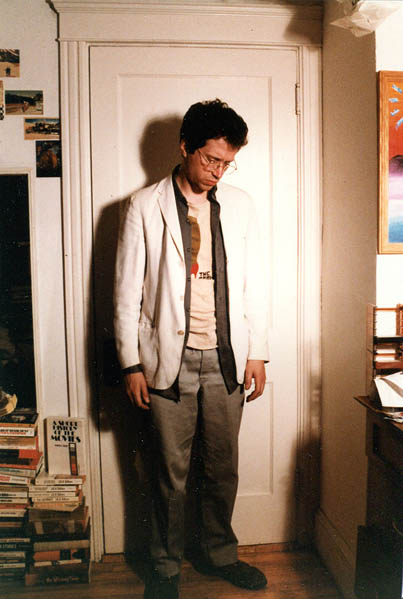

I never quite understood Laura’s remark about me and the biology lab.

Did I look like a scientist, or a science project? And that wasn’t my only beef with her Sweet Potato cover story about the Fashion Jungle.

The story’s opening is confusing, as she brings the reader from an FJ performance at Geno’s in the first paragraph to an FJ rehearsal in my parents’ basement, in the second, without ever announcing the shift in setting. Was Baked Fresh Daily playing at my parents’ house? I don’t think so! And things happened in the restrooms at Geno’s location on Brown Street that never happened in my parents’ bathroom.

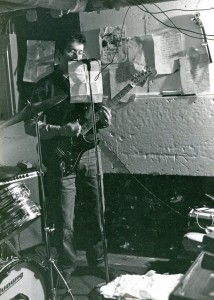

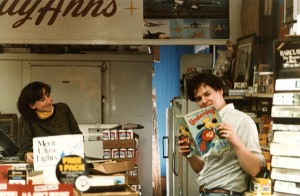

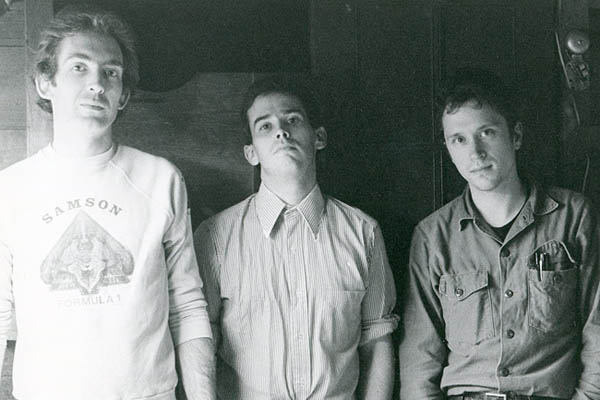

Ken Reynolds, “the band’s anchor behind the drumkit,” with the Fashion Jungle at the Maine Festival, August 1984. Click to enlarge. Image from Sweet Potato Magazine, courtesy of Rhonda Farnham Photography.

Butterworth also credits me with the lyrics to “Entertainer,” when in fact it was drummer Ken Reynolds who did the field research at the Stardust, a now-departed burlesque club on Congress Street, and then penned the musical query about a stripper’s state of mind.

Now a real estate agent and small-plane pilot who occasionally combines those skills, Butterworth was an impressionistic writer whose journalistic interests lay more in the fashion industry than in music. But the biggest problem with her article ― which, in truth, was very sympathetic to the band (and highly accurate when she credited us with “one of the finest arrays of original material that Maine has to offer”) ― was its timing.

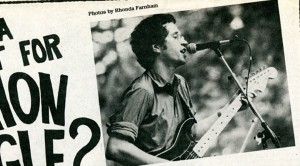

The FJ she portrayed was a band unhappy about its lack of commercial prospects, but still solid, forward-looking and fighting the good fight. That was the impression she got in August 1984, when she interviewed us and attended the rehearsal in South Portland. But needs and interests inimical to the band’s solidarity were in play even then. And by the time her article hit the newsstands, in late October 1984, nearly 28 years ago, the Steve Chapman–Kathren Torraca FJ was on the skids.

I must say, I’ve given a lot of thought to this particular post. It could easily become the mirror image of my chapter about the breakup of the original Fashion Jungle, which anticipated the Chapman-Torraca demise by three years, to the very month. The particulars were different, but not the underlying forces: the pressure to find meaningful or at least lucrative day jobs; the sense that Portland wasn’t the place to find them; and the youth-driven imperative to get the hell out of here (an imperative that I’ve felt, but only long past the end of youth and way too late to do much about it).

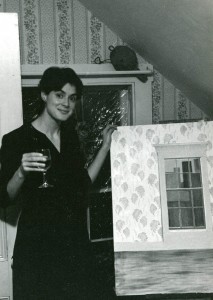

Escapee from a biology lab? How’s that again? Click to enlarge. Image from Sweet Potato Magazine, courtesy of Rhonda Farnham Photography.

Also the same, only elevated to a higher order of outrage because the band was sounding so good — and because, goddamn it, we’d been through this once already before — was my response: Why, oh why, did the band have to come apart just as things were starting to happen? I was furious then. I can still feel it. In my selfish view, it was just such a waste. It was too soon for it to be over.

I mean, look at it: We could play at Geno’s as often as we liked; in August, we performed at the prestigious Maine Festival, in Brunswick*; we had a recording on the market; we were getting media recognition from not only the local music paper, but the region’s two hip-and-cool radio stations, WBLM-FM and WMPG-FM. Surely there was more and better ahead.

And those were just the trappings of success. Most important, as the Geno’s recordings that accompany this post demonstrate, we were simply playing great — though it’s also true that for all of 1984, I was the only active songwriter in the band, and I was anything but prolific.

When Steve announced, at a late-summer party at Ken’s apartment, that he was moving to Boston to study computer science, I was upset but not surprised. The handwriting had been on the wall. The charms of cooking soup at a pub-grub eatery in Portland are not infinite. And Steve was in love with a woman from Boston.

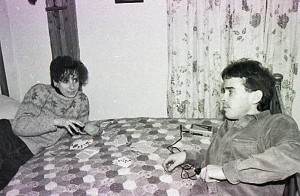

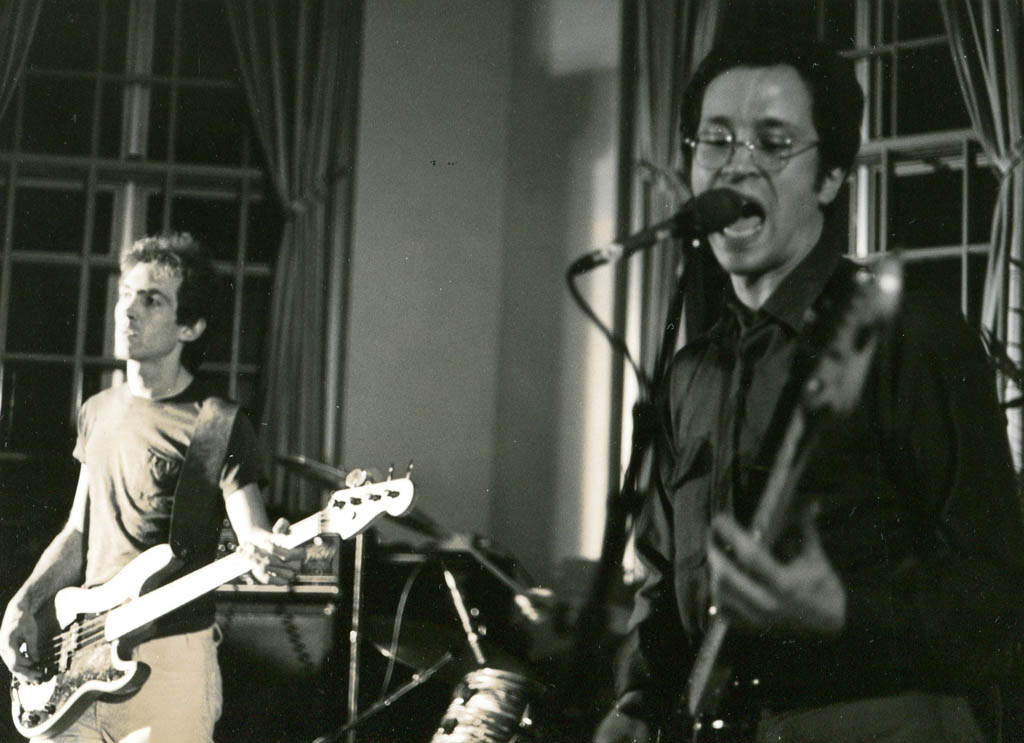

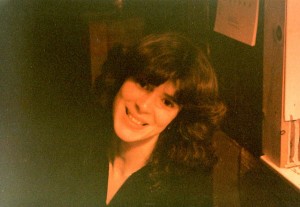

Keyboardist Kathren Torraca, at left, and bassist Steve Chapman with the Fashion Jungle at the Maine Festival, August 1984. Click to enlarge. Image from Sweet Potato Magazine, courtesy of Rhonda Farnham Photography.

Kathren was also restless, sick of her job, ready for higher education and a change of scene; we had been accepted at the Maine Festival while she was off on a European getaway, an absence that had made me wonder if we’d be able to do the festival at all.

And Ken was out of school and working part-time at the post office ― evenings. So much for the rehearsal schedule. And the switch to night work strained him physically and emotionally.

So in the autumn of 1984, there we were on the cover of Portland’s only music newspaper, smiling brightly, ready for fame if only it would come knocking. And there we were, not on newsprint but in reality, reduced to once-a-week rehearsals at Ben and Hattie’s, no new material coming in (we even tried Petula Clark’s “Downtown”; I still have Kathren’s “hits of the ’60s” songbook), the old stuff getting more and more leaden, everyone looking in different directions.

Jim Sullivan rejoined the band, playing mostly sax and commuting from Boston with Steve. Steve switched to a fretless bass. Each of those developments came with a learning curve that, by that point, just seemed insurmountable, though it was nice to work with Jim again. The four-piece band played Geno’s on Oct. 12 in a performance that I’ve spent 28 years thinking was our last; hear recordings from that gig at the links below.

And just yesterday I rediscovered in my notes that the five-piece band had a Geno’s date on Dec. 28. I have no recollection of it, to say nothing of a recording.

And that was that, really. Through the first five months of 1985 we continued to get together while taking turns declaring the end of the FJ: me because I was tired of the uncertainty, Kathren because she wanted to try different types of music, Steve because it was too difficult making it work from Boston — and he and Jim had gotten into a band down there, anyway; and Ken because the P.O. had hired him full time, evenings. But the particulars don’t matter. Endings declare themselves.

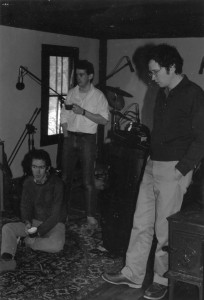

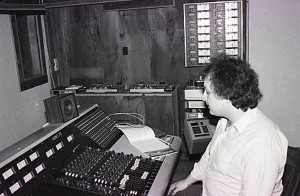

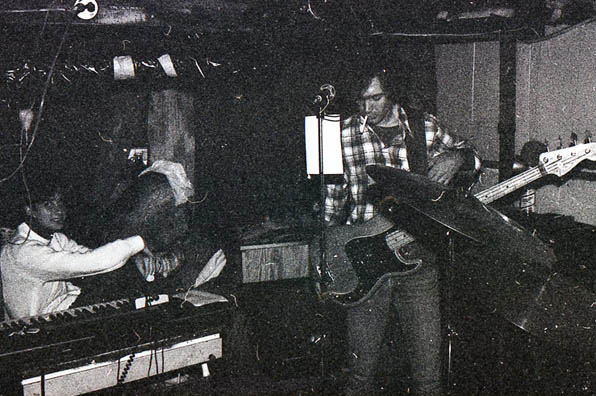

The Fashion Jungle at Geno’s, 1984. From left: bassist Steve Chapman, keyboardist Kathren Torraca, drummer Ken Reynolds, guitarist Doug Hubley. Photograph by Jeff Stanton.

Geno’s, Portland’s answer to the punk dive bar that every self-respecting city must have, is looking at its 30th anniversary in 2013, and merits its own post in this series. For now, though, all I can offer is this selection of seven songs from a performance, late in the life of the 1983-84 Fashion Jungle, recorded at Geno’s original location on Oct. 12, 1984. Rather distorted, hence the bargain-basement price point on the Bandcamp store. Recorded with two mics on a two-channel consumer-grade cassette deck ― it’s analog tape, kids!

- Pleasures of the Flesh (Reynolds-Hubley) Ken sings his lyric about a “friends with benefits” arrangement that ultimately rings hollow. Hot stuff, especially in the solos.

- Old Masters (Chapman) Steve’s commentary about the relationship between technology, culture and fine arts was the first song with lyrics that he contributed to the FJ.

- Coke Street (Hubley) In the 1980s, Portland’s Old Port Exchange was the go-go ’80s writ large and ornamented with seagulls. This country song with its odd lopsided rhythm was one of my rare attempts at social commentary, and one of my two compositions from 1984.

- Nothing to Say (Hubley) Art imitates life for five minutes. Compare with the Six Songs version. The guitar is the Rickenbacker 12-string.

- End of the Affair (Hubley) Always a passionate number, this was particularly poignant for me during this show, which I figured was pretty much the end of the FJ.

- Keep on Smiling (Hubley) A little too impassioned, maybe!

- Final Words (Chapman) An excellent performance of an excellent song. The tape runs out just as we segue into Steve’s equally fine “Curious Attraction.”

“Pleasures of the Flesh” copyright © 1984 by Kenneth W. Reynolds and Douglas L. Hubley. “Old Masters” copyright © 1982 by Steven Chapman. “Coke Street” © 2012 by Douglas L. Hubley. “End of the Affair” and “Nothing to Say” copyright © 1984 by Douglas L. Hubley. “Keep on Smiling” © 2010 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.

*I hope someday to present on this site Jeff Stanton’s film of that technically troubled but musically compelling performance.

Text copyright © 2012 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.