Fifty Years, Seven Chords and Some Truth

No time for pesky reading? Head straight for the Notes From A Basement store at Bandcamp!

What have I learned

about songwriting since 1969?

Not as much as one could have hoped. I still haven’t picked up enough music theory to use “jazz chords,” although at least I’m no longer afraid of them. Killer riffs? Forget it. My riffs don’t even like to argue.

Because I’ve never supported myself from songwriting, I haven’t learned to produce good songs when I’m not “feeling it.” For the same reason, I’ve never internalized the various kinds of self-discipline that go into crafting hits (as opposed to merely good songs).

For instance, a songwriting rule that I have trouble obeying is songwriter Harlan Howard’s observation, later elevated to the status of commandment, that country music is “three chords and the truth.”

Invoking the holy name of “truth” feels powerful, but that’s deceptive. Where does country music, or any genre of any medium, get off laying claim to truth, or is it Truth? Isn’t blues also three chords and the truth? (And maybe a truer truth, on average, than country, a genre that for all its greatness is still capable of producing toxins like “God Made Girls.”)

In fact, it’s actually true that truth isn’t really so scarce in creative work. Many songwriters remain true to themselves in their work even if their truth isn’t your truth. (And in any case, it’s also true that a grain of truth doesn’t make a pearl of every song.)

And if their truth is your truth, or something akin to it — or the song resonates with you even though the writer’s intention has escaped you altogether — then you can add your own truth to that particular heap.

I doubt that it’s possible to like a song without it striking some chord in your being, even if it’s just the urge to yell “Wooo!” And if you hate a song, that’s likewise reflecting something true in you.

It’s the “meh” songs that you have to feel sorry for.

So decreeing that a form of music (visual art, literature, etc.) has to be truthful in order to qualify for a label is like decreeing that a liquid must contain water to qualify as a beverage. It’s not really such a high threshold to get over. Ultimately, the “three chords and the truth” thing strikes me as more grandstanding or even defensiveness — “I don’t know many chords, but I speak truth” — than anything else. Go ahead and plant your flag on the hill of truth, if there’s any room left.

Therefore the truth part, while problematic, doesn’t challenge me as a songwriter. (And, again, since I don’t make my living from it, I can afford to wait for the True Ideas.) But that three-chord limit — wow, that’s tough. Five or six is more like it for me. Maybe it’s a good thing that I don’t use jazz chords.

This struggle with simplifying stems from both my relatively feeble melodic imagination — that is, I’m inclined to derive melody from chords and not the other way around; and my resistance to echoing the old and familiar, even if it’s familiar because people like it and people like it because it’s good. I’ll happy play the old, familiar and good if somebody else wrote it — but trying to emulate it in my own songwriting just makes me feel like a chump and a wanna-be. (And I get enough of that from walking past mirrors.)

Similarly, despite compelling evidence that compact song structures are generally preferable in the genres I play, rock and country, six- or eight-line verses and bridges tend to be my stock in trade.

But a few times I have managed to keep it simple (and didn’t even need the “stupid”). One example is my song “You Wore It Well.” After writing a string of songs that are country mostly because I say they are, I wanted to write something that came across as “country” all by itself.

Song structure was only one component of the exercise, but I made it work: four-line verses and bridge and, if not three, then four chords all told. And no minor chords! — quite unusual in my catalog. (See Recording Notes, below, for more information on the recordings linked here.)

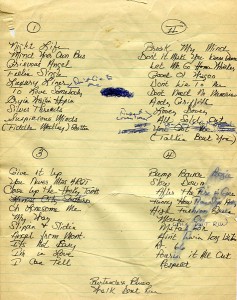

Something else I have learned since 1969 is to carry a songwriting notebook. This provides a place to store ideas, and a place to find ideas when you’re casting about for one. (And a place to revisit past failures and stalemates, but never mind.)

The concept for “You Wore It Well” — a song that uses things applied to the skin to sketch the course of a relationship — lived in the notebook for a while until, in a hotel room in Portsmouth, N.H., in February 2013, I roughed out some words. Four months later, in Cabin No. 19 at the Chautauqua in Boulder, Colo., during the afternoon quiet hours, “You Wore It Well” came together with a minimum of agony, as the better songs seem to do.

Another pretty good country song, despite all the songwriting lessons I hadn’t yet absorbed in 1977, is “Let the Singer.” I say “country song” despite its cryptic and fragmentary title and, even more transgressive, the chord count — seven, including both major- and minor-sevenths.

Seven chords and, yes, some truth. It’s not an especially macho howl, yet “Let the Singer” is a howl nonetheless — baying at the moon by a wolf who wants to join the pack. As angsty young guitarslingers will do, in those days I valorized the live fast–die young lifestyle and its practitioners, like Hank Williams and Gram Parsons.

It all seemed very romantic until so many musicians that I liked died young.

Thirty-eight years later I had developed a finer grasp of the effects that time and romance can work on one another. More concretely, in the helpful-advice category, I’d realized that you can plan out your song or skip the plan, but either way, it should sound like you skipped the plan.

For a few years I had wanted to write a song about three sounds that catch my heart’s notice: a train horn in the distance, pedal steel guitar playing especially by Sneaky Pete Kleinow, and the voice of my wife and musical partner, Gretchen Schaefer. But a number of writing attempts that hewed close to that literal theme went nowhere. They were too schematic. It was too much plan, not enough song.

Finally, in 2015, again at the Chautauqua, I wrestled the controls away from the conceptual scheme so that the words could go where they wanted. The result was “Just a Moment in the Night.” Gretchen, steel, and the train are all still there, but now as prominent elements in a larger tapestry depicting the pleasures and pains of passing time.

“The pleasures and pains of passing time” — vague much? Well, yes. Because I also learned, pretty early on, some reasons why many songwriters are reluctant to get specific about what their songs mean. That meaning, of course, is ultimately up to you, the listener. Why should I limit your experience of a song or pre-empt your imagination?

See, here’s a way to make truth, in the sense of “three chords and —,” work for you. It’s a lovely thing if the songwriter’s, singer’s and untold throngs of listeners’ truths all chime together as one. But even if only one participant’s bell is rung, that song has earned its wings.

So, just as it’s preferable not to talk too specifically about what your songs mean, it’s better yet when the songs themselves aren’t too prescriptive or obvious. It’s not fair to invite your listener’s imagination inside if there’s no place at the table for it.

Don’t tell ’em — don’t even show ’em — just strew the path with images and hints and fragments, and let the listener piece the story together into a truth of their own. (Bob Dylan being the master of this approach.)

I was waiting for an art history class to start in early 1981 when I wrote the line, “The only time you’re happy is when it’s right after sex.” That was the start to “Shortwave Radio,” which I finished on a June evening a few months later, with a gin gimlet sweating greenly on the glossy red table and The Bob Newhart Show, muted, on the television.

Although I do have a short but happy history with shortwave radios, I can’t explain how they came to symbolize something about my character in that song. (And if I could explain, as noted above, I wouldn’t.) But it was true at the time. And I’m just glad it happened because it’s a good song and it came along just as my band at the time, the Fashion Jungle, was scrambling for good originals.

The biggest challenge to Harlan Howard’s truth is the worst kind of schematic song — and country music abounds with them: the ones that get written because someone has been afflicted with a big stiff idea for a gimmick that must be gratified by wrapping a song around it, whether because a paycheck is dangling out in front of them somewhere or they just can’t get over themselves.

(I’d like to offer as evidence “A Boy Named Sue,” but its huge chart success meant that fans were mining a lot of some kind of truth out of it. And they’re digging deeper now. The title was adopted for both a documentary with a transgender protagonist and a 2004 book about the role of gender in American country music. So truth is as truth does.)

But sometimes a gimmick can be convincingly cleaned up and dressed in a decent suit. At least once, my weakness for wordplay started me on a song — “Where Was I,” whose cute “inspiration” resulted in a lyric that’s quite good, but not at all cute.

One day I got the Grass Roots’ hit “Where Were You When I Needed You” in my head — and “Where was I when you needed me?” seemed like a potentially meaty converse of it. The resulting lyric is cross-listed in the Themes of Country Songs index under both Cheating and Mid-life Crisis. (But the 6/8 rhythm and the melody would have sounded nice with the Stax rhythm section.)

A few guidelines are apparently helpful in songwriting, since here I am offering some, but as a non-professional songwriter I can indulge in the belief that much of songwriting success is out of my hands. I like to think that random combinations of time, place, season, weather, companion, political climate, frame of mind, mode of transport, historical interests, overheard remarks, current reading, prevailing odors, beverages at hand, etc., can, when you least expect it but maybe when you most want it, spontaneously coalesce into a song idea.

Which leads me to another lesson for songwriters (even though it somewhat weakens the previous edict about gimmicks): Don’t look a gift horse in the mouth. Song ideas are rare and precious. If something looks like a song idea (and doesn’t look like “A Boy Named Sue” or “May the Bird of Paradise Fly up Your Nose” or “Honky Tonk Badonkadonk”), grab it. (You don’t have to keep it.)

A likely specimen floated my way in summer 2019 via the intercom on an Amtrak train. We were stopped on a siding somewhere, not at a station, amidst trees in western Massachusetts.

It was June 2019, the train was Amtrak’s Lake Shore Limited and we were headed west on a single-track mainline. A voice on the intercom announced that we were waiting for an eastbound train to clear the track. So we sat and waited, as we have done many times before.

But the rhythm of that announcement — “We’re waiting for an eastbound train” — struck me. I wrote those words in my songwriting notebook in hopes that some actual song idea would come along and keep them company.

Sure enough, a few days later, while Gretchen and I were sitting on the back porch of No. 19, back at the Chautauqua, I wrote “(Waiting For A) Westbound Train.” What a gift: A nuisance for an Amtrak conductor and his passengers that sparks a new song for me, my first and last in 2019. I prefer gifts (most of the time) that don’t come at other people’s expense, but when it comes to bolstering my glacier-paced songwriting output, I can’t be fussy.

You will notice the directional change, from eastbound in the conductor’s announcement to westbound in the song. Between the alliteration, which is nothing to be sneezed at in songwriting, and the fraught and many-layered symbolism of East vs. West in the American mythology, I had to bend the facts to suit the reality. “We’re headed back East as we always must be / To the same old and the good old and the old used-to-be.”

Fifty years almost to the month prior to “Westbound Train,” in 1969, I wrote the first song that I thought was any good. Its inspiration was simple: my relief at breaking up with a perfectly nice girl whose only offense was to be around when I was feeling hemmed in.

Well, I was 15 and the song, “Glad to Be Free,” sounds in every way like the product of a 15-year-old. But though I’m not linking to it here, not will I likely ever sing it again (way to clear the room in a hurry!), I still regard it as the start of my credibility as a songwriter.

And what my oldest and my newest song (and some of the good ones in between) have in common is their rootedness in a real and immediate situation — a teenager out of love who’s moving on, riders on a train who’d like to move on. Small realities, way back in 1969 and just last summer, but they’re my realities and that’s what I have to work with.

That’s country songwriting the way I do it: seven chords and some truth.

Recording notes

(Waiting For A) Westbound Train (Hubley) In a September 2019 rehearsal in the Basement, Day for Night performs a real anomaly in my recent songwriting output. In a word, it was speedy in every way: The idea, inspired by a conductor’s announcement on Amtrak’s Lake Shore Limited, came to me in a flash. I wrote the song in a couple of days, as opposed to the usual two or three years from conception to completion. And Gretchen Schaefer and I learned it fast, too. Doug Hubley, vocal and lead guitar. Gretchen, vocal and guitar. Written in Boulder, Colo., in June 2019. “(Waiting For A) Westbound Train” copyright © 2019 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.

Just a Moment In The Night (Hubley) Day for Night again, during that same charmed rehearsal. The middle section of this song comes from the outro of my 1983 song “Nothing to Say.” Written in Boulder, Colo., in June 2015. Personnel as above. “Just a Moment in the Night” copyright © 2015 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.

You Wore It Well (Hubley) From a Day for Night rehearsal in September 2016. Personnel as above. “You Wore It Well” copyright © 2014 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.

Where Was I (Hubley) From a November 2013 Day for Night rehearsal. Personnel as above, except Doug switches to mandolin. “Where Was I” copyright © 2014 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.

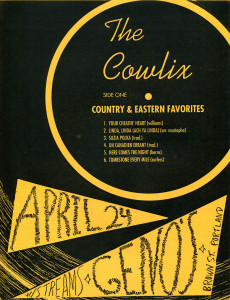

Let the Singer (Hubley) The Curley Howard Band premiered the song in 1977, but this recording was made two years later by the Mirrors at our first gig, at Jim’s Night Club, on Middle Street in Portland, Maine. With Ken Reynolds, drums, and Mike Piscopo, rhythm guitar. “Let the Singer” copyright © 2010 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.

Shortwave Radio (Hubley) Leonard Cohen once told an interviewer something to the effect that performing “Bird on a Wire” reminded him of his duties somehow. When my bands were electric, “Shortwave Radio” played a similar role for me, albeit involving not duties as much as, simply, why I want to be in music. This stayed in the repertoire for more than 20 years, from the Fashion Jungle to the Boarders — heard here, in a 1996 rehearsal — to Howling Turbines. Gretchen Schaefer, bass. Jon Nichols-Pethick, drums. “Shortwave Radio” copyright © 1981 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.

Notes From A Basement copyright © 2012–2020 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.